Yes, What We Pay Teachers Matters

Paying teachers well is an essential part of a healthier public education system

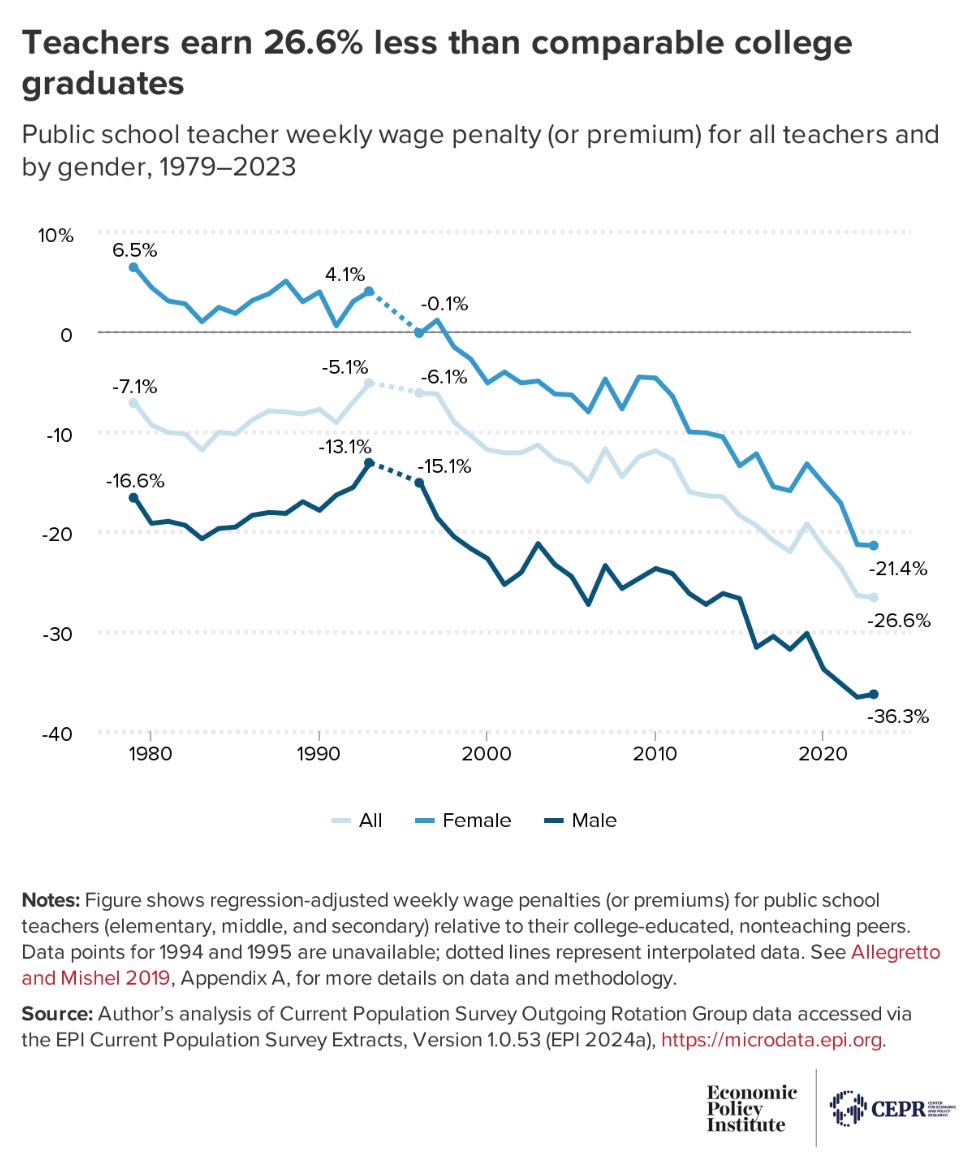

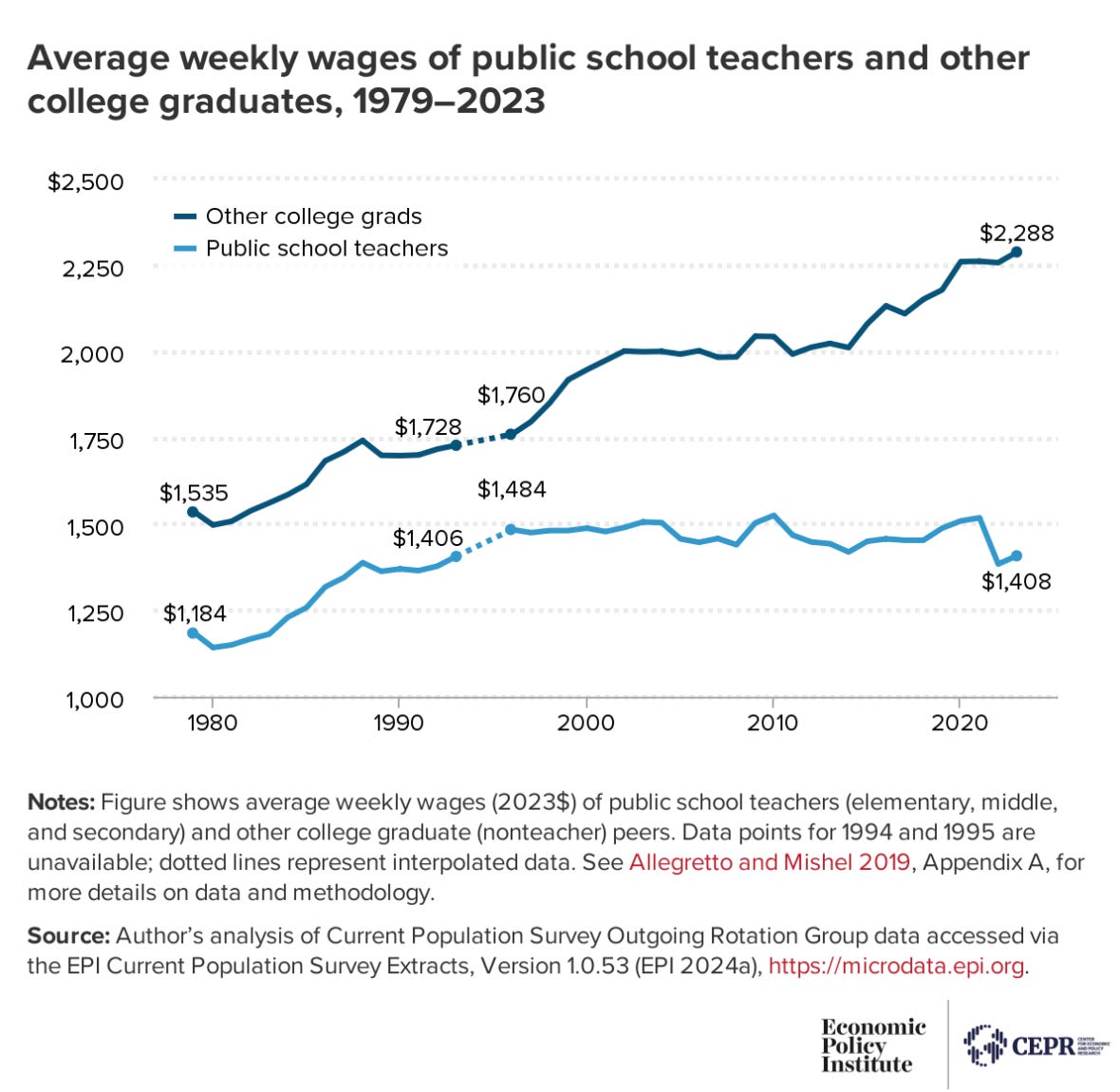

Public school teachers once took home salaries in line with workers in similar professions. Through the eighties and into the nineties, they paid a small penalty for choosing to teach; in 1993 the average salary of teachers was about 5% lower than that of others with college degrees. A new report by economist Sylvia Allegretto at the Economic Policy Institute reveals that three decades later, that penalty has grown to nearly 27%—an all-time high.

This penalty has worsened as teacher salaries began a prolonged stagnation.

There are those on the right who argue that this gap isn’t all that meaningful. A recent piece in Reason tries to downplay the impact of the teacher pay penalty by pointing out that averages obscure state-by-state differences. It’s hard to see how this helps their case, though, when teachers pay a penalty in every state and when more than a dozen states across various regions—New Hampshire and Colorado, Oklahoma and Oregon, Georgia and Arizona among them—pay penalties worse than the national average.

Opponents of raises for teachers frequently claim that teachers’ benefits balance out their low pay, but Allegretto’s analysis shows they don’t. When total compensation packages are accounted for, the teacher pay gap is reduced, but only to 16.7%.

Then there’s the argument that teachers aren’t motivated by money. From Reason:

Adding to the murkiness, pay doesn't seem to motivate teachers as much as many people think. According to a December 2023 report from the National Center for Education Statistics, when public school teachers were asked why they decided to leave the profession, only 9.2 percent said it was because they needed higher pay.

A closer look at the NCES data reveals that excluding those who leave for personal reasons such as retirement or health, needing or wanting better pay is one of the most important factors in teachers leaving the profession, second only to wanting a job in another field (which itself could involve pay considerations).

For over a decade, I’ve been talking to teachers about why they teach. Their first answer is never about pay. It’s about the joy in seeing the light of understanding in a student’s eye, the pride in hearing from former students about their impact, the desire to contribute something positive to community and country. We can thank goodness that so many derive this satisfaction from their work.

But while promoting teaching as a calling rather than a profession has facilitated the logic of austerity in education spending, it’s not smart. Because teacher retention is just part of the story. If we want healthy, vibrant public schools that serve every student, we need to improve recruitment of new teachers, keep and distribute the best teachers, and support teachers at every phase of their careers.

Young people’s interest in education continues to slide as they recognize “many downsides” to teaching, including its unattractive pay. High school and college students have other reasons for being less interested in the field. One is the lack of respect they would expect, and new research says they aren’t wrong: Matthew A. Kraft and Melissa Arnold Lyon found “perceptions of teacher prestige have fallen between 20% and 47% in the last decade to be at the lowest levels recorded over the last half century.” Another is the lack of autonomy teachers are afforded.

These non-pay reasons can, though, be connected to low pay. Teachers have become subject to decreasing autonomy as teacher shortages and less qualified hires have pushed some districts toward scripted lessons and other forms of micromanaging. Teacher bashing by right-wing politicians and media has helped keep both wages and respect for teachers lower than they should be.

Of the ten states with the worst teacher shortages, the majority have pay penalties worse than the national average. But across the nation, shortages are worst in high-poverty schools, where teachers tend to be paid less. Given that these are the schools serving some of our most vulnerable children, teachers in them should be paid more—a lot more. Instead, we have had decades of chronic underinvestment in schools, particularly in urban and rural areas. This is the case in red states and blue states, as decades of austerity have denied lower-income neighborhoods and towns the resources for decent infrastructure and staffing.

Teacher shortages are both a recruiting and retention problem. The solution is not either/or: Keeping the best teachers requires competitive pay and better working conditions. I’ve written elsewhere about some of the bad ideas going around about how to solve the teacher shortage and about how some working conditions can be improved so teachers can teach more effectively. The only evidence of teachers being paid and treated poorly is not the sound of doors slamming behind them. We should be at least as worried about the effects of teachers working under stress or moving between schools as we are about them quitting the profession.

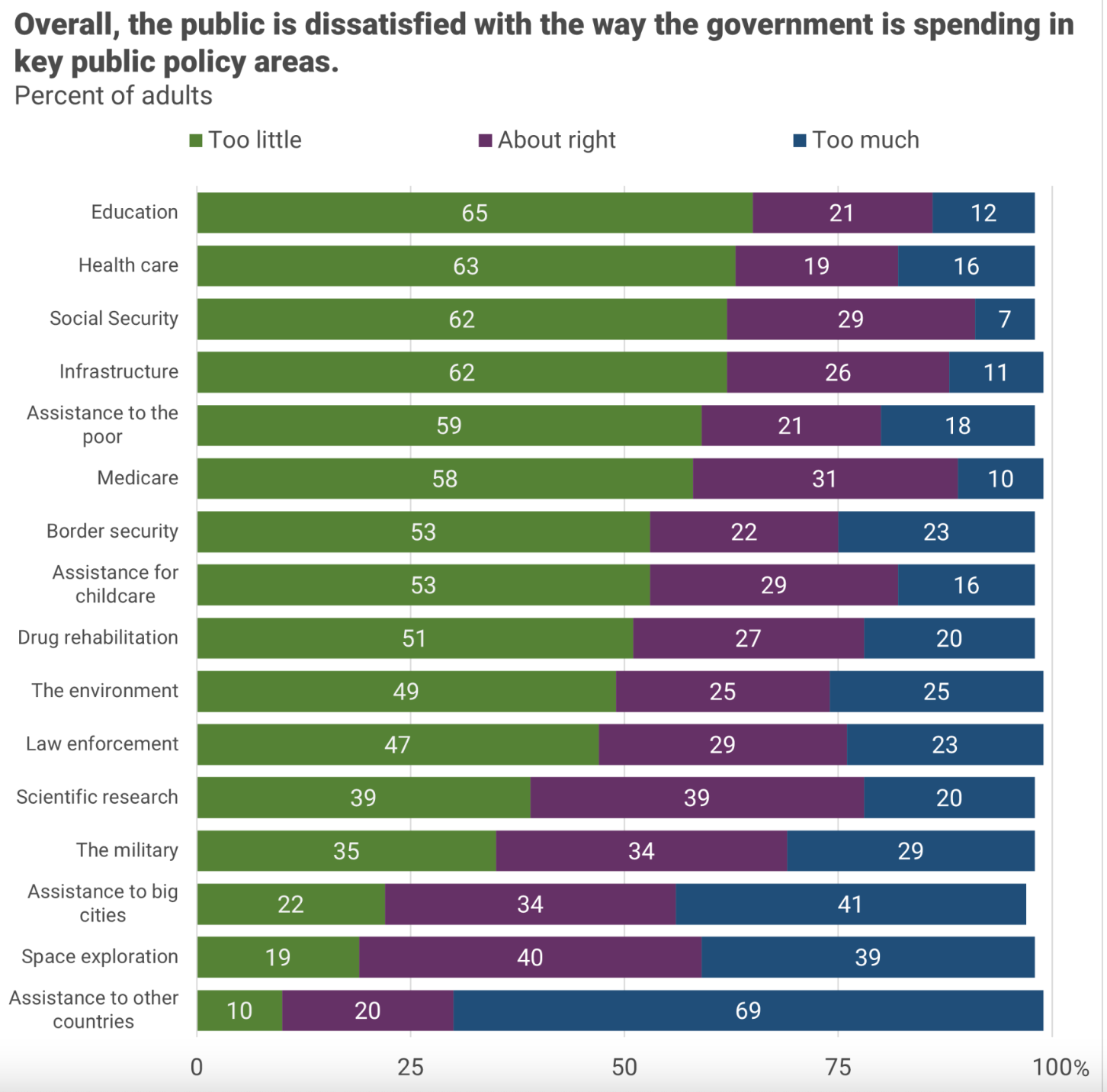

Americans understand the importance of healthy, energized, effective teachers, and they understand that our teachers tend to be underpaid (even if they sometimes overestimate by how much). And research across 31 OECD countries shows that 1) students learn the most from educators with strong cognitive skills and that 2) countries that pay teachers better are able to employ teachers with higher cognitive skills. In other words, teacher pay matters.

Americans want more government funding for education. Republicans are answering this call not with funding for public schools and teachers but by diverting dollars into private school voucher programs that make it harder for public schools to pay for the staff, facilities, and supplies that students deserve, and in some cases, harder to stay open at all.

North Carolina, for example, currently ranks 38th in overall teacher pay. Following a trend in red states, the North Carolina legislature is about to pass a $463 million education bill that denies a 2% requested raise for teachers in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools but provides tuition dollars for private schools to families, including many well-off ones. Although some states have included teacher raises as bargaining chips to pass voucher legislation, the residents of state after state are finding their budgets being busted by school vouchers. Arizonans are facing a $1.4 billion shortfall largely as a result of its voucher program, which advocates had claimed would save money.

Who benefits from these sweeping voucher programs? Not the 83% of American children who attend public elementary, middle, and high schools. And few of the children from struggling schools. As I’ve written about previously, most vouchers go to the affluent, to families with students already enrolled in private schools, and to religious institutions. And as education policy expert Josh Cowen shows in his new book, The Privateers: How Billionaires Created a Culture War and Sold School Vouchers, some participants don’t benefit as academic outcomes of voucher programs have declined and “the most vulnerable students suffer high turnover—or are pushed out of voucher schools.”

A second Trump Administration would likely harm public education budgets and worsen the teacher pay penalty, as Project 2025 promises cuts to federal education spending. A recent Brookings piece explains how low-income students in red states would suffer most if the Project 2025 agenda is successful. And of course, the appointment of more Supreme Court justices by Trump increases the chances of further pro-privatization judicial action.

While it explicitly acknowledges the need for better pay for teachers, the 2024 Democratic Platform is light on details for K-12 education, but Democrats up and down the ticket are the hope on the ballot this fall. More Democrats in Congress would have saved $100 billion in school infrastructure spending from being cut from Biden’s Build Back Better bill. With a Democratic POTUS, a former teacher as VP, more members of Congress, and more Democratic governors, public schools could receive more of the attention they deserve.

No, not all teachers are terribly underpaid and not all areas are suffering teacher shortages. But waving away the teacher pay penalty and the chronic underinvestment in public schools from which it arises is irresponsible and unresponsive. The US is a wealthy nation whose citizens value public education. We can argue about the best ways to fund and pay enough to recruit the best and the brightest into the system fully and equitably. But we don’t get a world-class education system by pretending teacher pay doesn’t matter.