When British fashion designer Mary Quant died this week at 93, her obituaries focused on the groundbreaking, youthquaking miniskirts and dresses that made her famous. Quant was responsible for popularizing them worldwide in the 1960s, but as she put it: "It was the girls on King's Road who invented the mini. I was making clothes which would let you run and dance and we would make them the length the customer wanted.”

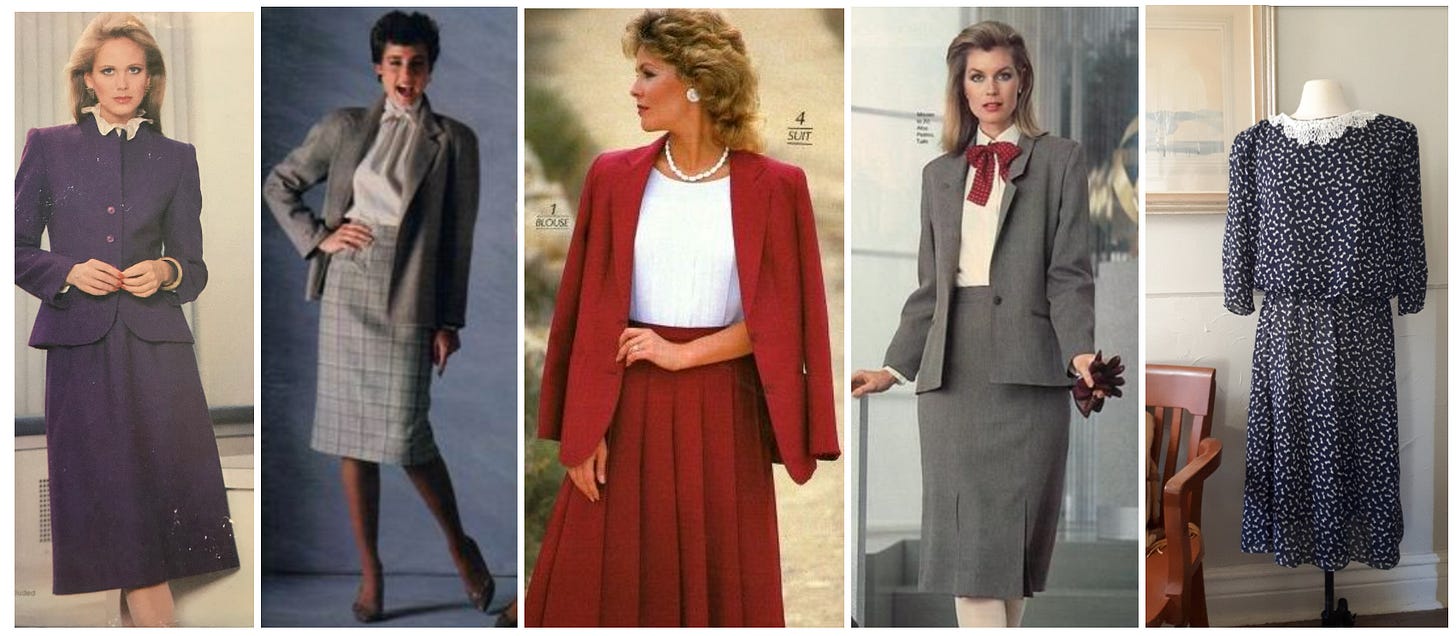

I was reminded of the first mini-skirt revival, which arose during my college years in the 80s. Inspired by the fashion magazines I studied as though an exam followed, I shortened all my hems. But after graduating and starting a career in business, Monday to Friday meant hiding away not just my knees but elbows, collarbone, even neck. Two decades after Quant’s breakthrough, comfortable and fun women’s fashions were relegated to the weekend. At work, we were expected to wear holdovers from the 70s, suits with below-the-knee skirts and calf-length dresses that were safe, dull, and involved a lot of fabric. The required panty hose and heels ensured discomfort.

As the 80s wore on, hems inched up at work. (After all, something had to be done to balance the ever-growing shoulder pads.) The first time I went to the office in a skirt that stopped above my knees, I was so nervous the memory crystallized in hi-res (glass corner office meeting, Manhattan skyline beyond, the boss is smoking a cigarette, the skirt is navy blue). By the early 90s, women’s departments carried a lot of pantsuits, but women at my new workplace weren’t buying them. Another vivid memory is of three of us plotting (hush-voiced by the water cooler in a midsized building in a midsized city in the Midwest.) If we all started wearing pantsuits on the same day, it would be okay. It was okay — but we had a real sense that it might not have been.

We had been told to dress for the job we wanted, not the one we had, and the few women senior to us were playing it safe. Of course, most of the executives who had the jobs we wanted were men, and they were all trousered. Why the resistance to women’s pants? The panic over a shorter skirt was more leg. Pants meant less. But the mini was never verboten because it showed too much skin — opaque hose ruled in Quant’s time and the 80s. It was about denying women the choice.

I haven’t worked in the corporate world for more than two decades; when I left for a new career in teaching, casual Fridays were a thing and slacks and a cardigan or blazer had become my go-to. Has getting dressed become less fraught since? One website for interns informs them of four dress codes offices may follow: business professional, business casual, smart casual, and casual — and to confound things, “variants” on these and “other in-between” codes. The career services department at a B-school unencrypted the “business professional” dress code with a list of dos and don’ts for women that is more than twice as long as the one for men. It seems it’s still easier for women to get it wrong. And the very existence of gendered dress codes sets tripwires for those who are nonbinary or gender nonconforming.

Switching from a male-dominated profession to a female-dominated one should have brought me relief, but dress codes in schools can be their own kind of hell. A relaxed dress code for teachers is rare enough to make it an effective recruiting tool. There were no rules against wearing jeans in my districts, but one principal stared disapprovingly each time I did. Teachers in some schools can earn as a special treat or pay for extra “jeans days,” a nauseating, infantilizing maneuver that says, “We don’t really believe this clothing item interferes with teaching. We’re withholding its comfort as leverage.”

As some businesses have loosened explicit rules in recent years, some school districts have tightened them. Waukesha, WI introduced a stricter code earlier this year by instituting a business casual code for staff, focusing in a memo on prohibited items: tee shirts, jeans, sweatshirts and pants, flip-flops, sneakers, hats, caps, and my favorites: “tight or ill-fitting clothing” and “clothing that shows excessive skin.” It’s not incidental that roughly half of the administrators responsible for enforcing this code are men; roughly three-quarters of the teachers subject to it are women.

An educator’s recent tweet suggesting that dressing more professionally could lead to teachers being treated with more respect went viral before he wisely deleted it. As one responded, particular clothing choices aren’t going to garner respect from those who don’t grant it to teachers based on credentials and experience:

We live in a society that still makes judgments based on small differences in attire. One study showed that people perceived (models posing as) doctors to be more experienced and professional when they wore traditional white coats— but males scored higher than their female counterparts in every outfit. The idea that dressing a certain way will produce esteem from sexists was a fantasy in the 1970s and it remains one today.

It pains me to even write about dress codes for students, which can extend beyond clothing to grooming, and have long been instruments of gender, sex, religious, and racial discrimination. Discipline for violations is meted out disproportionately to girls and students of color:

GAO estimated that 93% of school districts have some kind of dress code or policy, though not all of them are considered "strict." More than 90% of those rules prohibit clothing typically worn by female students: items such as “halter or strapless tops,” “skirts or shorts shorter than mid-thigh,” and “yoga pants or any type of skin tight attire,” the report says. Meanwhile, it found that only 69% of districts were as likely to prohibit male students for wearing similar clothing, like a "muscle shirt."

As Andre Perry explained after a Black senior in a Texas suburb was suspended and kept from his own graduation ceremony for wearing dreadlocks, dress codes can be ways to “control and suppress.” Students in one Wyoming community were reportedly told they could no longer wear rainbow pins or bracelets or even clothing in rainbow colors; since this incident in 2019, GOP legislatures have passed laws making it easier for schools to use dress codes to clamp down on political speech and self-expression. Of course, it’s not just schools: a spate of anti-drag bills seek to control how people express themselves through their clothing in any public place.

It’s hard not to get discouraged: nearly six decades and four generations after Mary Quant and the Boomers raised Cain with raised hemlines, young people are still experiencing attempts to grind them down by policing what they wear.

But there are rays of hope. Black girls in D.C. produced a report about the impact of dress codes for the National Women’s Law Center and went on to fight for fairer policies in their schools. Nadra Nittle wrote last year at The 19th about a wave of student activism in her piece “Lawsuits, complaints and protests are upending sexist school dress codes.” And just weeks ago, Education Week reported on female high school runners who, after being suspended from play for wearing sports bras to practice in excessive heat, worked to overturn the dress code that had penalized them.

I dare to say Mary Quant would approve.