The trailer for Feud: Capote Vs. The Swans touts it as “The Original Housewives.” But that’s not what drew this guilty viewer of Bravo’s Real Housewives to the FX series, which aired its sixth of eight episodes last week.

Growing up in the 70s, well before I’d read or assigned his writing, I knew of Truman Capote, whose image appeared among the glitterati in magazines. I saw Murder by Death, clueless then as to why he’d been cast as a vengeful party host. He’d gone to my high school, where my dreadful emo poems appeared in the literary magazine that had published his work decades earlier. Finally, I read Breakfast at Tiffany’s, then In Cold Blood, and later, more by and about him. I named a cat after To Kill a Mockingbird’s Dill, based on Harper Lee’s childhood friend Truman.

Capote died at 59 in 1984, the year I headed from college to Manhattan with modest delusions of a glamorous life. (Too small and poorly raised to be a swan, I could hope to be a stylish imp.) And now I’ve outlived him. This may be why I’m experiencing Capote Vs. The Swans not as nostalgia but as memento mori.

A fictionalized account of Capote’s split with his high society patrons and friends, Capote Vs. The Swans smells of escargot and chardonnay and cashmere and fine leather but most of all it reeks of death, only some of it social.

In this way, it is nothing like Real Housewives, where the women can seem less than real in part because the franchise treats death, rather than life, as fleeting. Aging, death’s advance team, is kept at bay with fillers, surgery, and glam squads. Death makes only cameo appearances. A cast member’s beloved parent passes away, but the show quickly pivots from the loss to petty arguments. An estranged husband dies by suicide, and that becomes fodder for a catfight in which the wife’s grief is denied.

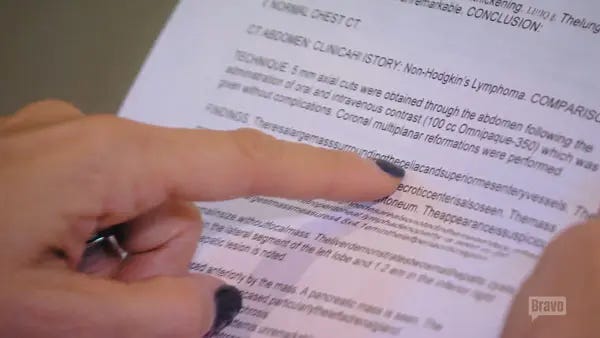

Illnesses too tend to be doubted and dismissed, as though disease itself can’t possibly be real. Yolanda Hadid’s struggle with Lyme became a storyline because other Beverly Hills wives questioned whether she was as sick as she said. This season’s Real Housewives of Miami echoes the theme with one cast member’s assertion that another, battling breast cancer, “fakes the most tears.” One health story that dominated a season in Orange County was an actual case of fraud exposed by wives interrogating a boyfriend’s cancer claims. The Housewives universe is meant to be filled with entertaining trifles, conflict so unserious that it can be waged over a fancy dinner and won or forfeited by the next day.

Capote Vs. The Swans offers the beauty and fashion, the lavish lifestyles, the gossip and scandals, but it doesn’t provide for looking away from death. Despite a narrative structure that shuttles back and forth in time, the series moves inexorably toward it. In an early episode, the Babe Paley character (Naomi Watts), lead socialite or “swan,” contracts lung cancer, and while the ladies avoid the topic of her illness at their standing lunch date, it permeates the room like second-hand smoke from the cigarettes she draws on between treatments.

The pacing of key scenes is as slow as cancer treatment, as slow as the medicine that makes its way, in recurring close-ups, through IV tubes. When chemo is done, there is radiation. We watch Babe meticulously groom, dress, and bejewel herself only to realize she is headed to the hospital where she’ll shed these regal trappings to don a paper gown and lay face down on a cold machine, an X drawn on her delicate back. In the doctor’s office with her, we learn the tumor is not shrinking. She will die. She asks when. The doctor does not answer.

Babe begins to give away her jewelry, extravagant pieces gifted in lieu of fidelity by her husband during a marriage as unhappy as it is glamorous. Before Truman Capote (Tom Hollander) betrays her and the other swans by publishing their secrets in Esquire, the series suggests, his companionship is one of the few joys in her life, a life that will be cut short.

Capote’s painful descent into alcoholism is an invitation to death, imagined as a danse macabre with his late mother (Jessica Lange) at his celebrated Black and White Ball. The social ostracism the swans deliver as punishment for his betrayal accelerates the downward spiral. As an abusive lover assaults him body and soul, loneliness and alcohol attack his mind, font of the words and wit that had brought him attention and admiration.

Capote’s self-destruction seems like it may be completed in the fifth episode with a suicide attempt, but he is saved by a phone call from James Baldwin (Chris Chalk), who spends a day with him acting as a motivational speaker. This interaction, which didn’t occur in real life, uncomfortably employs, as Fletcher Peters puts it in The Daily Beast, the “racist cliche” of a Black character existing “in order to magically solve” a white protagonist’s problems. Yet the episode serves to deliver a key message of the memento mori.

While Babe reminds us that life is short, that luxury and status are no substitute for a well-lived life of any length, Baldwin’s role is to demand that talents be used and purposes be fulfilled. He wants Capote to continue the work of the article that won him censure, not for individual revenge but to be in community with the vulnerable and expose the evils of the social system. (Given how pointedly personal are the series’s Capote’s concerns, the suggestion could seem absurd, but the author’s In Cold Blood delivered a powerful argument against a justice system that metes out death.) Baldwin tries to call him back to a generative life.

And it is a good call. Capote’s earthly pleasures are at this stage highly transitory—and not all that pleasurable. Seducing a younger man, string-pulling for a protégé, making a spectacle at Studio 54, going in for plastic surgery—and most of all, trying to regain the social stature he gambled away—are sad attempts to turn back the clock. But of course he’s not that old! Fifty-somethings can have decades ahead of them to give and receive love, to apply their talents, to be in the world and help shape it. Of the many causes of Capote’s downfall, vanity is the ultimate villain. It renders him incapable of these things.

With two episodes to go, we don’t know the ending but we know the ending: a man well known for his genius becomes perhaps better known for the way he wasted it. There are several reasons to watch Capote Vs. The Swans (not one of them is to cheer up), but the best is for the reminder that we get only one spin on this distracted globe, and if we can get out of our own heads, we can be in our age, be in the time we have.

Postscript: This heartbreaking piece by Babe Paley’s granddaughter is worth reading. It’s a reminder of the real lives behind fictionalized versions of them.