The Home Economics of Lib-Owning

Fear, identity politics, and going broke for conspiracy theories

The right has long focused on the protection of objects that symbolize, for it, freedom. A couple of flags come to mind, sure, but more often lately these objects are random appliances such as gas stoves, which were taken into sudden embrace earlier this year by freedom fighters such as Jim Jordan, who elevated them by tweet to the Holy Trinity — “God. Guns. Gas stoves.”

No regulation meant to reduce pollution or mitigate climate change is too modest or obscure to escape becoming fodder for right wing politicians or their media. This can seem laughable, as it did when Trump launched into a weirdly poetic rant about toilets allegedly needing to be flushed a dozen times. In a recent segment on new washing machine regulations, a Fox news guest conjured Grimm’s-level images of her children afflicted by hair conditioner as a result of low-flow showers. Steps to save energy are presented as an obliteration of choice and an impingement on freedom. Meanwhile, the washing machine standards in question may “save U.S. consumers up to $14.5 billion over 30 years.”

The conflation of consumerism with freedom has led to a politicizing of waste that has been costly for American households — and no product shows this more dramatically than the automobile. Before this turn to home appliances and plumbing products, right wing pundits and think tanks and the fossil fuel interests who love them were at work protecting America’s cars and trucks — all 291 million of them — from an imaginary war on cars.

Early and often, automakers have encouraged American buyers to associate cars with independence. And it worked, as Catherine Lutz and I learned talking to car owners for “Carjacked.” Despite a lot of Americans having no choice but to drive in a landscape built for cars, many became convinced by decades of heavy marketing spending that their vehicles were freedom machines.

The owners we spoke to also tended to see cars as modes of self-expression, something car companies were pushing hard in the late aughts when we began our research. Many believed that cars, distinct from other household appliances, should communicate their complex identities and serve as a kind of “social skin,” to use the words of Terence S. Turner. These identities included a variety of statuses and attitudes, including, to some extent at that time, political identity.

A recent piece in the “Financial Times” by John Burn-Murdoch revealed how expensive identity-driven shopping has since become, especially for the Republican base. Burn-Murdoch referenced research showing that Republicans buy more new cars than Democrats and are far more likely to buy larger SUVs and trucks. The average price of a new car in 2022 was an eye-popping $45K — 55% more than the average used car (even in this hot market for used cars). The average price of a new full-size pickup truck: $60K. Of course, the costs of vehicle ownership go beyond purchase price, and the larger the vehicle the higher the costs of insurance, maintenance and repairs, taxes, and, usually, gas. If I bought a 2023 Chevy Suburban with a purchase price of $66.5K, it would cost me $80K over five years to own and operate it.

Overspending on cars by Republican leaners is driven by particular attitudes that automakers have been happy to cater to as they facilitate the sale of larger and more expensive vehicles. As Burn-Murdoch put it:

The divide becomes even more stark when Americans are asked to pick which attributes they look for in a new car: “aggressive”, “powerful” and “rugged” all rank among the top five selected by Republican-leaning purchasers. The US fleet of huge vehicles is down to identity, not necessity: individualism on wheels.

This isn’t necessarily an individualism born of confidence. Since 9/11, automakers, like the Republican Party, have tapped into deep fears about national and personal security. When I spoke for “Carjacked” to Sheryl Connelly, Global Consumer Trends and Futuring Manager at Ford Motor Company, she told me the carmaker saw a nation fearful of crime and terrorism and distrustful of institutions, a combination making some car buyers feel it was “incumbent on the individual to take care of themselves.”

While GOP politicians have encouraged their base to buy military-grade guns and ammunition as they fear-monger about crime, automakers have understood that feeling unsafe is “very fluid,” as one Ford exec put it to me, in and outside of the cars they were selling. Owning and driving an “aggressive,” “powerful” and “rugged” vehicle may be an expression of a desire for freedom, or it may be reflective of fears and the wish to conquer them.

Both the GOP and the auto industry have sought to position themselves as providers of safety in a dangerous world. Research shows gun owners feel more in control of their lives when reminded that they own guns; owners of over-sized vehicles likely feel similarly. Automakers understand that for this segment of the market, feeling safe means feeling threatening: “We spent a lot of time making sure that when you stand in front of this thing it looks like it’s going to come get you. It’s got that pissed-off feel,” the designer of the GMC Sierra HD explained.

For some, it’s not enough of a statement of political identity to buy and drive steroidal vehicles. In the mid-teens diesel truck owners began rolling coal on Prius drivers, a multi-sensory way to celebrate waste. Polluting to own the libs! And when Trump voters took to the roads in trucks before the 2020 election, in one case swarming a Biden-Harris campaign bus? Traffic-jamming to own the libs! Like fantasies about toilets that won’t flush and stoves that don’t cook, much of this can seem silly. And does it matter if someone wants to overpay for vehicles? What they do with their money is between them, GM, Allstate, Wells Fargo, and Exxon.

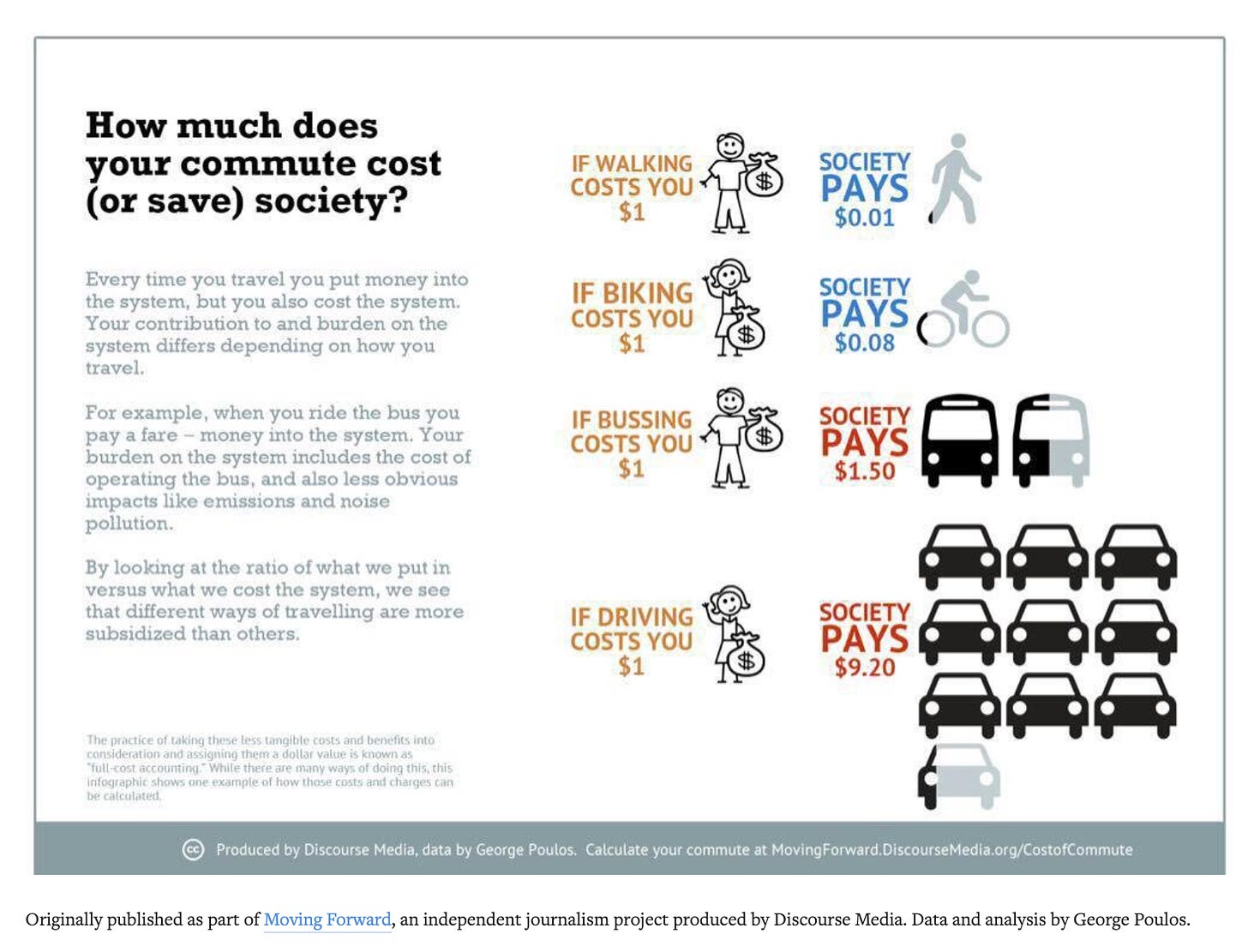

Unfortunately, while some are being convinced to empty their wallets for a false sense of control, we all pay in a variety of ways. When 9 of the top 10 vehicles sold are SUVs and trucks, all of us breathe air that is more polluted, experience more extreme weather events, suffer other outcomes from climate change. And bloated vehicles (whether gas-powered or electric) don’t just look more dangerous, they are: They put drivers of smaller, lighter vehicles — and especially pedestrians and cyclists — at greater risk of injury or death in a crash. We all pay for the fossil fuel subsidies required to keep gas prices artificially low. We all pay more for other, already high externalized costs of driving including road maintenance and parking and crash response and clean-up.

Critically, when consumer products become entwined with political identity, those who profit benefit from the political will those consumers can create or suppress. Gas prices can help decide elections. Equating car ownership with American freedom makes it harder to regulate the fossil fuel, car, and other industries for public health and safety. It makes it harder to fund the transit that could reduce pollution and climate change — and reduce excess traffic, which costs the average driver $1,377 a year. It makes it harder for municipalities to pursue options that can make residents happier, healthier, and wealthier. Planning by cities and towns for increased walkability has turned into the global conspiracy-theory-du jour. Just Google “15-minute cities” to see how one sensible response to cars’ public health effects has become the latest panic of the anti-mask, anti-vax crowd.

The Great Recession seemed like a moment that would help Americans understand how much they were overpaying for vehicles at the household level. But since then, as Millennials have been chastised for overspending on avocado toast and lattes, many of their parents have been modeling how not to save for a rainy day by continuing to invest in the very expensive depreciating assets parked in their driveways. I haven’t given up on the idea of improving financial literacy around cars, but it can only do so much for those who want to rationalize irrational purchases.

Advocacy around transportation alternatives often does and must focus on the tangible, visible benefits* to rational drivers and car owners of 1) having the choice to leave their cars behind even some of the time and 2) other drivers having the choice to stay off roads more often — since one of the reasons people across the political spectrum buy larger or multiple vehicles is that they feel forced to spend so much time in them. One of the bright spots of the pandemic were so-called “open streets” in cities like New York, some of which have been made permanent. The more Americans see the benefit of investing in transit, complete streets, and returning more land to people, the more political will there can be for regulating an auto industry that has played an outsized role in environmental havoc and appears to have found a way to profit from political division.

*I’m more convinced than ever that happy warriors like Streetfilms’s Clarence Eckerson, based in New York City, and others doing similar work across the country are a crucial part of the answer. Eckerson’s videos make the benefits of safer streets and less driving — including the emotional benefits — tangible and visible. You can donate here to Streetfilms’s umbrella organization or find a group in your area.