The Grip of the White Savior Story

“The Blind Side,” "To Kill a Mockingbird," and captivating tales of race and rescue

I never read “The Blind Side” for the same reason I never saw the movie: feel-good is not my genre. I also never told a student it was a good idea to write about a text they hadn’t read or seen, but I’m going to do something like that here—as the news surrounding them has overtaken both book and film.

Lawsuit and Controversy

Michael Oher is the ex-NFL player whose young life provided the material for “The Blind Side,” Michael Lewis’s nonfiction book and the based-on-a-true-story movie starring Sandra Bullock. He recently filed a lawsuit against the Tuohy family, assumed by many—including, Oher alleges, himself—to have adopted him. He claims they withheld profits from him and that he was misled into a conservatorship at 18, half his lifetime ago.

Details in the suit—and in the responses of the Tuohys and their lawyers—are not feel-good. While he alleges he believed he was signing the adult equivalent of adoption papers, conservatorship could conceivably enable Oher’s treatment not as a family member but as a commodity. When the story first broke, Yale law professor Stephen L. Carter wrote about the case in The Washington Post:

At the time Oher moved into the Tuohy home, rumors were swirling of well-to-do White families adopting talented Black kids and persuading them to play sports at the parents’ alma maters. The NCAA investigation of this possibility is basically where the movie starts. The “feel good” aspect of Oher’s story is supposed to be that in this case, the love was real. If it all turns out to have been a sham — well, that’s about the saddest ending The Blind Side could have.

It will be more than sad if it is discovered the Tuohys’ love was “a sham,” but the story of the story is already bad.

The Tuohys say they split modest profits from the film five ways, “an equal amount for each family member,” giving Oher a fraction of the monetization of his life story and keeping the rest. It speaks to how the story of a young Black man, after being written by a White author and rewritten by a White screenwriter, became the story of a White family.

On the conservatorship issue, Insider's Yoonji Han explored how “ableism and racism can intersect to prop up a ‘white savior’ narrative.” And Oher has long argued that the film dismissed his teenaged drive and capabilities and depicted him as “dumb.” Just as a conservatorship could allow the real Tuohys to take agency from the real Oher, a narrative that presented the fictionalized Oher as mentally limited allowed the fictionalized Tuohys to play outsized roles in “The Blind Side,” to rise from among the pivotal figures in his life to the status of white saviors.

The “White Savior Industrial Complex”

While the Tuohys’ lawyer suggested the couple couldn’t have made money at Oher’s expense because they were already rich (as if wealth prevents people from wanting to be wealthier), The New York Times found they profited from their white savior status:

Leigh Anne Tuohy has leveraged her fame to become a motivational speaker, charging $30,000 to $50,000 per appearance, according to available online estimates.

The Tuohys’ Making It Happen foundation, which pledges to help children who “fall through the cracks of society,” has brought in more than $1 million since 2010, including some donations from Sean Tuohy’s businesses…The foundation has spent less than 20 percent of its total received donations on charitable efforts…

A decade ago, Teju Cole posted about the “White Savior Industrial Complex” in a Twitter thread responding to the Kony 2012 phenomenon, when a video prompted a flurry of White Americans to demand justice for Ugandans, in sudden “[f]everish worry over that awful African warlord.” But as Cole explained, “The White Savior Industrial Complex is not about justice. It is about having a big emotional experience that validates privilege.”

That experience came to some from watching the video, but to others from simply hearing or reading about it, posting about it on social media, and participating in the shared experience of exclamation. The White Savior Industrial Complex draws in many due to its psychic rewards; it meets, as Cole put it, “sentimental needs.”

In a subsequent piece in The Atlantic, Cole argued the charitable work of the advantaged enables them to ignore systems sustaining the status quo beneficial to them. These systems can be obscured too, of course, for the broader audiences of stories in which White protagonists rescue people of color deemed defenseless and deserving. “The Blind Side” became a cultural phenomenon in the 2010s as the movie attracted Oscar nominations and the bestselling book populated book club and school reading lists. As Steve Almond predicted in his review, it would “play to the masses as an inspiring underdog saga, spiced with proper pieties about the power of hope and individual destiny.” Its “big emotional experience” delivered reassuring messages to those made uncomfortable by American inequalities. But as Almond went on, “It should also stand as an inadvertent testament to the national blind spot that still prevails when it comes to our racial pathologies.”

The Classic Complex in Schools

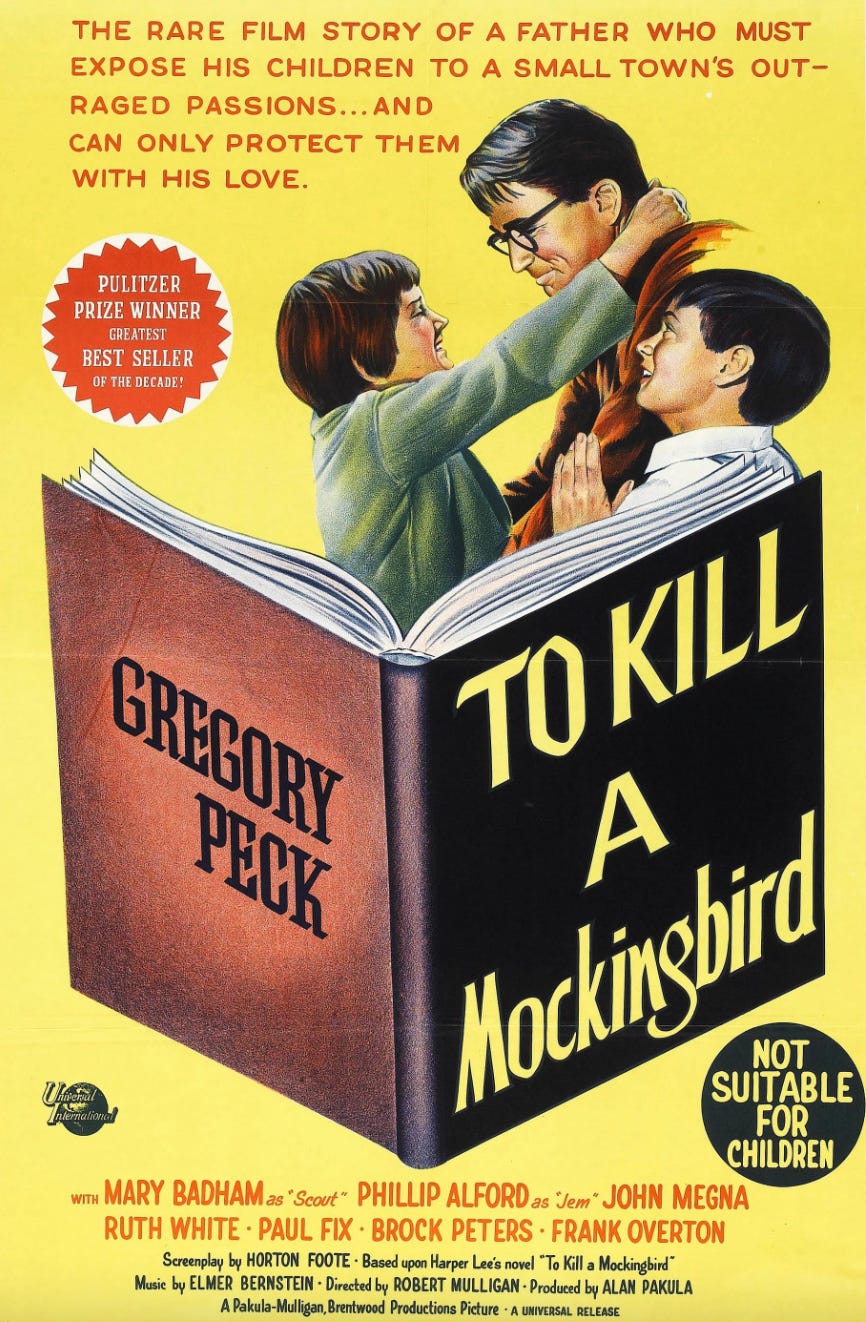

Two decades ago, when Michael Lewis was writing “The Blind Side,” I was teaching Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” to four sections of mostly White eighth graders. It had long been required reading at the school, and my students seemed the right age for it: the reading level was challenging, they found it engaging, and it tied into the History curriculum, which covered Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Movement. One lesson asked students to analyze minor characters. Some would choose Tom Robinson, an annual reminder to me of how at odds his status in the book was with his importance to it—without Tom, the novel doesn’t have its conflict, its plot, its title, its themes. They couldn’t choose Tom’s children; there was too little to analyze. The reader spies them late and briefly, though they get to know so many other young people: Scout and Jem and Dill and Walter and Burris and Mayella.

We’d discuss who the main character was: Scout, the narrator? Atticus? The Finch family? Maybe Maycomb? There were a few options, but none were Tom Robinson. And, of course, the story doesn’t end when Tom’s life does. Instead of leaving the reader’s lingering sympathies with the Robinsons, the conclusion hands them to the Finches. The focus at the end is on the cost of Atticus’s bravery, with hope and redemption arriving in the form of Boo Radley, a White man. “To Kill a Mockingbird” provides much realism, exposing horrors, injustices, and hypocrisies of American racism, and the white savior fails to rescue the Black character from a racist society. Nevertheless, the novel ends with this particular feel-good moment.

I stopped teaching the book when I left that school in the late aughts. Over the following decade, publishers put out more works by writers of color and schools brought more of them in. Some teachers have replaced “To Kill a Mockingbird” and some schools have taken it off required reading lists, usually because of the repetition of racial slurs, which regardless of planning and care taken, can cause great pain to Black students. This has led to accusations of book banning by the left.* But it is the backlash to the displacement of white savior narratives—or the simple addition of books by Black authors centering Black characters alongside white savior narratives—that has played a role in a wave of book bans and wider education censorship given teeth by GOP-dominated legislatures.

I’ve been thinking for the past few years about how the current generation of right-wing book banners has largely left “To Kill a Mockingbird” unchallenged. They do this in part, I venture, because some progressives have challenged it, allowing them to both-sides the debate about educational freedom. It’s also because across the political spectrum “Mockingbird” is the most widely-read and beloved white savior narrative in American literature. Today’s right-wing doesn’t want to keep children from reading about and discussing race. They want them doing it in ways that allow White children to have Cole’s “big emotional experience” while avoiding the buzzkill of learning about the persistence of systemic racism.

Historical fiction can allow for that avoidance. When Harper Lee wrote “To Kill a Mockingbird” in the 1960s, she set it in the 30s. Hollywood’s recent white savior narratives also tend to be set in the past, putting racism safely in America’s rearview mirror. This includes two mentioned in Han’s piece:

The white savior trope is problematic because it "promotes white dominance and white superiority," according to Chad Dion Lassiter, race relations expert and executive director of the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission. Lassiter cited "The Help" and "The Green Book" as other examples of films promoting a white savior narrative.

"It seduces us into the Black-white binary of thinking that it's the only way Black humanity can overcome the challenges they're faced with," Lassiter told Insider. "What's absent from that narrative is the systemic and structural racism that creates all these conditions, like mass incarceration and trauma."

The “divisive concepts” or “anti-CRT” or “anti-woke” laws that passed in dozens of states over the recent years use some variation of the following language: students must not “feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race, color, sex, or national origin." As CNN paraphrased Florida Democratic State Senator Shevrin Jones, these bills are “an attempt to revise history and keep White people from feeling uncomfortable.” Yes, it’s a culture war designed to gin up votes, but the GOP officials passing these laws don’t appear to want children to “connect the dots or see the patterns of power” that connect the present to the past.

The current backlash has gone well beyond saving white savior narratives from context; we are now witnessing an attempt to rewrite slave narratives. In Florida, it’s not enough to make students comfortable with their relationship to the nation’s history of slavery. Children are to be taught the “benefits” of slavery. Propaganda videos approved for school curriculums include one that invents a speech excusing it and, hideously, puts the invention in the mouth of a cartoon Frederick Douglass: “I’m certainly not OK with slavery, but the founding fathers made a compromise to achieve something great: the making of the United States.”

Noah Berlatsky summed up the white savior narrative as “Black people are oppressed by bad white people. They achieve freedom through the offices of good white people. Happy ending.” Full stop. Right-wing censors seek to compress the plot structure of America’s white savior narrative so tightly that it bends back on itself. America’s racism has been solved; it was always being solved.

It’s not just the right, though, that needs to move past the white savior narrative, as the wide popularity of “The Blind Side” shows. Some adults remember “Mockingbird” as key to their adolescent consciousness-raising around race; they respond to the very idea of the book today with the same emotional intensity, wanting to keep it on required reading lists. But white savior narratives, new or old, do not give today’s students the chance to contend with race deeply enough. Instead, they provide the model for the full stop the right wants to impose on discussions of race. Moving past personal and ahistorical nostalgia requires deepening understanding of American racism via works by authors and filmmakers of color. “The Blind Side” controversy is a reminder of the ugliness and messiness that its kind of tidy story obscures.

*A book is not banned if it is removed from required reading lists but is still available in the school for teachers to teach and/or students to read. This hasn’t stopped right-wing book banners and some journalists from continuing to “both-sides” the debate over book bans. “To Kill A Mockingbird” has been challenged but has rarely been banned.