November 3, 1976. I walk into my junior high Social Studies class and over to the football player who’s been boasting for weeks that Gerald Ford had the election sewn up. I smile and hold aloft my offering: a small bag of peanuts.

It’s a vivid memory, this analog act of trolling. Growing up in a very Democratic family in a deeply Republican town, I hadn’t before known what it felt like to win.

The moment came midway through the decade that shaped those of us in Generation Jones. As Jennifer Finney Boylan explained:

We might be grouped with the baby boomers, but our formative experiences were profoundly different. If the zeitgeist of the boomers was optimism and revolution, the vibe of Gen Jones was cynicism and disappointment. Our formative years came in the wake of the 1973 oil shock, Watergate, the malaise of the Carter years and the Reagan recession of 1982.

Now, with the passing of some of its longest-living key figures, the seventies may finally be coming to an end. Last week we bid good riddance to Henry Kissinger, “chief architect of…agony,” who hit a century without being held to account. It’s hard to characterize a decade that ended with this man boogieing down at Studio 54 as anything but one of “cynicism and disappointment.”

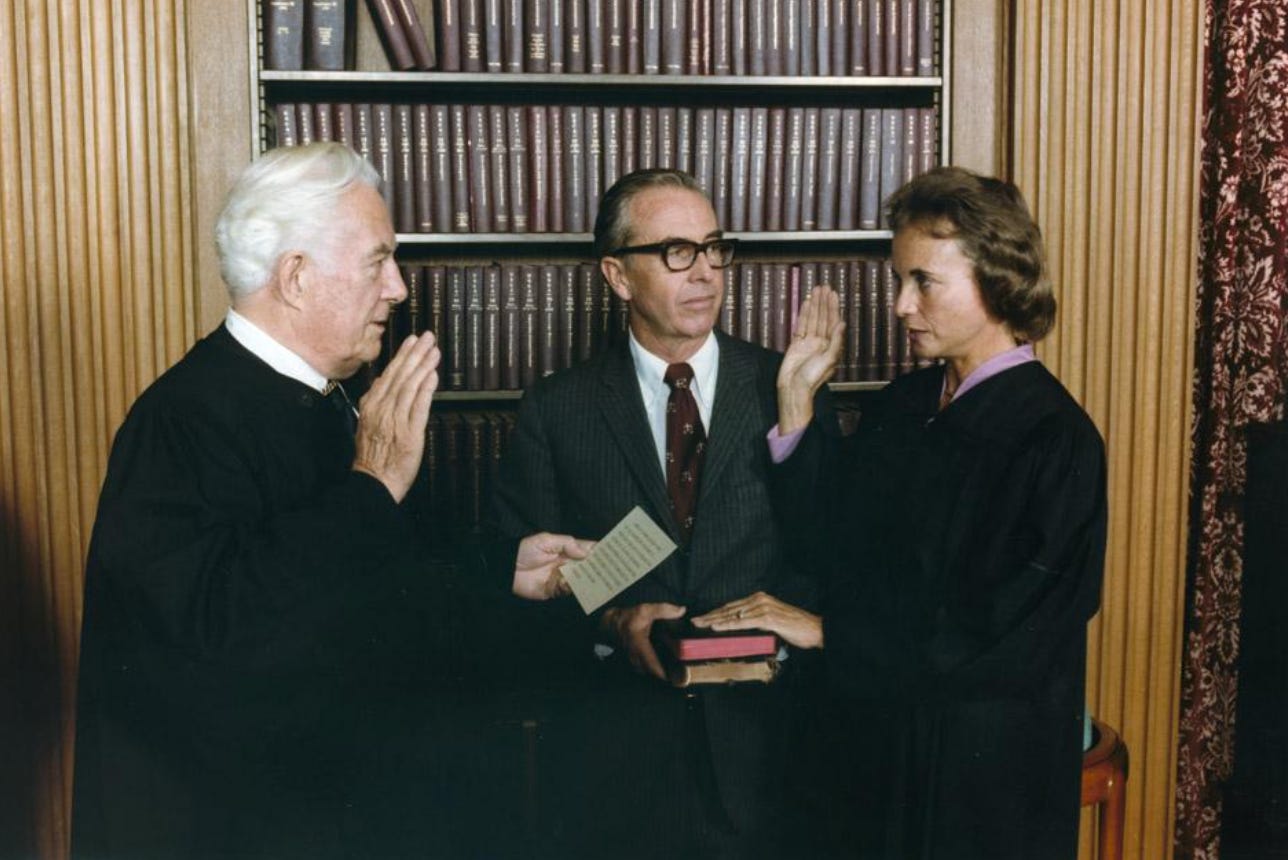

Yet the recent loss of Rosalynn Carter and Sandra Day O’Connor and the imminent loss of Jimmy Carter are reminders of leaders and events from those years that provided tremendous hope: a profoundly good couple installed in the White House and the first woman elevated to the Supreme Court among them.

One the main reasons I grew up with hope: the women’s movement was succeeding. I came of age with less fear because effective contraception became more available and Roe versus Wade became law. Advances that would later ensure me greater control over my adult life were already liberating women. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act passed in 1974, allowing women credit cards in their own names; a wave of no-fault divorce laws made bad marriages easier to dissolve. The fight for the ERA was all over the news, suggesting further progress to come.

Inspiring role models were everywhere. I watched Shirley Chisholm run for president, Billie Jean King beat Bobby Riggs, Helen Reddy sing “I Am Woman,” and Mary Richards make a city her own. I watched my mother, after having mostly raised six kids, go to law school, pass the bar, and begin work as an attorney. I watched friends’ mothers leave damaging marriages for happier, more productive lives. I watched my older sisters head off on diverse paths to college, career, and family.

Women won a lot in the 1970s. Nothing makes that more clear than current efforts to roll back those wins, including the criminalizing of abortion, restrictions on contraception, and calls to eliminate no-fault divorce.

The 1970s saw the expansion of other rights and protections now under existential threat. The Voting Rights Act was extended and amended under two Republican administrations. The Environmental Protection Agency was established, enabling huge strides toward a cleaner America and healthier Americans. Even some of the darker moments in the decade appear brighter in light of recent history: the Watergate hearings and trials brought some justice and a peaceful transition of power.

My grief at losing the Carters has surprised me. I know it’s personal, my feelings for them enmeshed with my feelings for my late parents, who shared many of their causes, especially preserving the environment and securing water, food, and shelter for people in need. It’s more than that, though. Yes, Jimmy did submarine duty and my father flew in World War II, but what placed the two couples in a generation that could be called “Greatest” was their later political and charitable work—work local and global, bold and incremental, cooperative, intersectional, and unprofitable. I fear their spirit, this idea of greatness is also passing.

In a speech late in his presidency, Carter described a “crisis of confidence” in the country. He shared his worry that Americans’ belief in pulling together to solve economic, social, and environmental problems had been weakened. “Our people are losing that faith, not only in government itself,” he said, “but in the ability as citizens to serve as the ultimate rulers and shapers of our democracy.” Four and a half decades later, these words do more than ring—they blare.

After that speech, his opponents accused him of lacking hope and faith in America. Carter never lost hope or faith, but his was the kind that requires a commitment to work. The speech outlined what he meant to accomplish on energy policy, but he also asked the public to do what they could, which was to conserve. Too many voters preferred the message of his opponent, who offered a dreamy vision of a future that didn’t directly ask anything of them other than a singular tick on a ballot.

In an essay this week, a political analyst dumped a truck of reasons—including unaffordable housing, education, and health care—why the US has become a country in which it is harder to live. Among other things, she bemoaned the same culture of consumerism Carter critiqued in his speech. But as Jamelle Bouie pointed, the litany of problems, long and legitimate, was unmet by a call for collective action. The author’s solution: buy property overseas and pack her bags.

I, too, have talked glibly about a hasty exit to another country. It’s something beyond privilege. It’s succumbing to the same fantasy that authoritarians peddle: It’s a losing game, but you can win, to hell with everyone else.

By spending too much time on the odds rather than the stakes, to use the language of NYU’s Jay Rosen, some in the media present our elections as games.* But they aren’t games to be won and gloated over (put those peanuts away) or lost and humiliated by. Elections are the way we choose who will work for us and with us. As the seventies ended, voters chose not the candidate who warned of the dangers of a government detached from the people and knew what democracies need to thrive. Instead, they chose a man made-up and coiffed to look like a winner.

Focusing on the odds makes elections about candidates when they should be about citizens and the issues we want to tackle together. It turns voters into consumers who need to be sold a product (see the umpteen stories about whether Biden can turn out the youth vote) instead of citizens who seek information to make informed decisions. That conception—voter as consumer—has convinced some that withholding their vote is a power move, that not doing something is doing something.

The media, campaigns, activists, citizens all have work to do between now and November to communicate the stakes. One party is prepared to gas-fire the project of reversing the progress made during our lifetimes—and our parents’—with a candidate who calls Americans “vermin” while praising the brutal leaders of other nations. The other party seeks to continue that progress with a candidate who respects our people’s ability “to serve as the ultimate rulers and shapers of our democracy.” No amount of malaise or cynicism or disappointment should ready us to give up on that.