Return to the Office Nightmares

On work, empty office buildings, and not turning back

A recurring nightmare I’ve had for decades: I am compelled to return to the Wall Street bank that hired me after college. I worked there twice, ten years in all. The second time I quit, my boss tried to keep me from leaving, joking that “it would be too embarrassing to come back a third time.” It’s possible he cursed me with the dream.

In it, I’ve returned to the bank for that dreaded third time and things are going badly. Wandering office-lined halls, I recognize few holdovers from the old days while fresh replacements in the bullpen grind on, paying me no mind. I am a kind of ghost, but the pressure is palpable. A boss somewhere expects something, but my job description is vague, and I’m floundering. Worse, I am without a key card to access the green-glass tower, so each day I have to sneak back in through the turnstiles standing guard before the elevators. Much of the dream revolves around this fraught returning.

When in Manhattan now, I find myself peering into buildings like the ones I worked in. Beyond glass, lobbies wait, encased in stone. Because I usually visit on weekends, they tend to be eerily empty. I get a whiff of the nightmare’s dread, revive the memory of pushing through revolving doors and turnstiles and ascending the elevator to work, including on weekends, when the lobby was vacant but for the brief transit of the unlucky called in on the wish or whim of someone senior. It’s those days I remember most. The quiet. Waving a hand to the others already there, cups of diner coffee adding more rings to their blotter calendars.

Over the years of its nocturnal reappearance, the turnstile became a well-worn metaphor in my personal narrative. Office turnstiles serve as security gates, keeping out those who don’t belong. I never felt I belonged in that field, its male-dominated, make-or-break atmosphere fostering impostor syndrome. Yet in the haze and hazing of its long hours, the work was all-consuming; office life was life. My next career, teaching, was a better match. Nevertheless, I continued to have the nightmare, and even now that I’ve left teaching, I still sometimes wake from facing the turnstiles. I keep going back to having to go back.

The flood of news and opinion on remote work has me thinking anew about turnstiles, imagined and real, as many profiteers, politicians, and pundits try to herd more people back into offices while some workers want nothing less. Here are some pieces from just the past week about working from home (WFH):

“Return to Office Enters the Desperation Phase” (New York Times)

“Bosses Are Fed up With Remote Work for 4 Main Reasons. Some of Them Are Undeniable” (Yahoo Finance)

“The Founders Want You to Work From Home” (Washington Monthly)

“‘I Feel Like I’ve Missed Out’: Has Working From Home Thrown the Gen Zs Out With the Water Cooler?” (Guardian)

“Working From Home Becomes a Once-a-Week Perk for Some Office Goers” (Bloomberg)

The winners of the week have to be the dueling tabloid stories “Swollen Eyes, a Hunchback and Claw-Like Hands: Grotesque Model Reveals What Remote-Workers Will Look Like in 70 Years” (Daily Mail) and “Shocking 3D Model Reveals What ‘Damaging’ Remote Work Could Do to Our Bodies” (NY Post). The unsurprising twist to this shocker? The “experts” who produced this nightmare material are employed by an office furniture manufacturer.

Employees who prefer remote work have been subjected to a barrage of contradictory messages over the past few years about its wisdom, but being subjected to images of potential deformity from working in allegedly unhealthy workspaces—their own homes—takes it to a new level. (It’s stories like these, BTW, that make me miss The Twitter That Was. Oh, the fun we had.)

After the laughter subsides, what remains is the pointlessness of trying to scare office workers this way. Those who prefer remote work know going into the office means similarly spending too many hours sitting at a desk staring at a screen and tapping away at a keyboard—with the addition of hours of unhealthy driving and breathing unhealthy office air. (I can’t help noticing that “Anna,” The Hunchback of Remote Work, suffers legs crossed with varicose veins. My first one appeared my first year at the bank. My doctor told me to put a box under my desk to elevate my legs.)

The back-to-the-office chorus has been throwing everything against the wall, exploiting shame (You think you’re special? You’re lazy and want to shirk!) and fear (Your skills will atrophy! Your hard work won’t be noticed! You’ll miss out on advancement opportunities! Your job will be cut!). Much defies logic, like Elon Musk’s claim that all remote work is “immoral” because not all work can be done remotely. Along the way, WFH opponents have raised the stakes from the personal to the corporate to the systemic. It’s not just their own jobs and companies that workers are told they’re threatening by wanting to work at home. Now it’s entire cities and regions and the nation they’re putting at risk, and everyone should be alarmed and resentful.

This spring’s “New York Times” op-Ed by investment banker and “Morning Joe” chart maven Steven Rattner drew a lot of lines between dots. The headline “Is Working From Home Really Working?” suggests that WFHers aren’t really working and that they are the architects of a doomed national economic project. Connecting a preference for remote work with workers’ rising desire to avoid being overworked, Rattner calls both signs that Americans are becoming “soft”—a sexist dog whistle that relies on the devaluation of work in homes as insufficiently tough and manly:

The question lurking in the minds of many with whom I’ve spoken (as well as my own): Has America gone soft?

A recent Wall Street Journal report noted that in a Qualtrics survey of more than 3,000 workers and managers, 38 percent said the importance of work to them had diminished during Covid and 25 percent said it had increased…

Stimulus checks and less-than-normal spending during the worst of the pandemic encouraged these trends. At its peak, Americans had $2.1 trillion more in their bank accounts than customary; today they still have about $900 billion of excess savings.

Rattner, who was worth $188 million when he was Obama’s "Car Czar" in 2009, thinks his fellow citizens are "soft" if they don’t want to impale themselves on the sword of living to work and working to spend. Didn't want to die on the job during pre-vaccine Covid days? SOFT! Actually nest-egging funds for security in the midst of a global crisis? SOFT!

But the enemy is both weak and strong. Because while American workers are soft, Rattner tells us they are also strong enough to be determining the future of the entire economy. He goes on to blame them for the future lower “standard of living” he predicts will result from their “choice,” assigning the modest pushback of some US workers against overwork more power than the full force of the Chinese government:

But we should be aware of different choices being made in other countries, particularly China, our biggest strategic adversary. The Chinese expression “996” means working 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week. While the Chinese government has been trying to curb this practice as part of a series of labor market reforms, in my many interactions with businessmen and investors there, I still find the prevailing work ethic extraordinary.

Indeed, according to the Wall Street Journal report, the property manager JLL found that office occupancy in Asia ranges from 80 percent to 110 percent (meaning that in some cities, more staff members are in the office than before the pandemic). By comparison, U.S. office occupancy stands at 40 percent to 60 percent of pre-Covid levels, lower than even Europe...

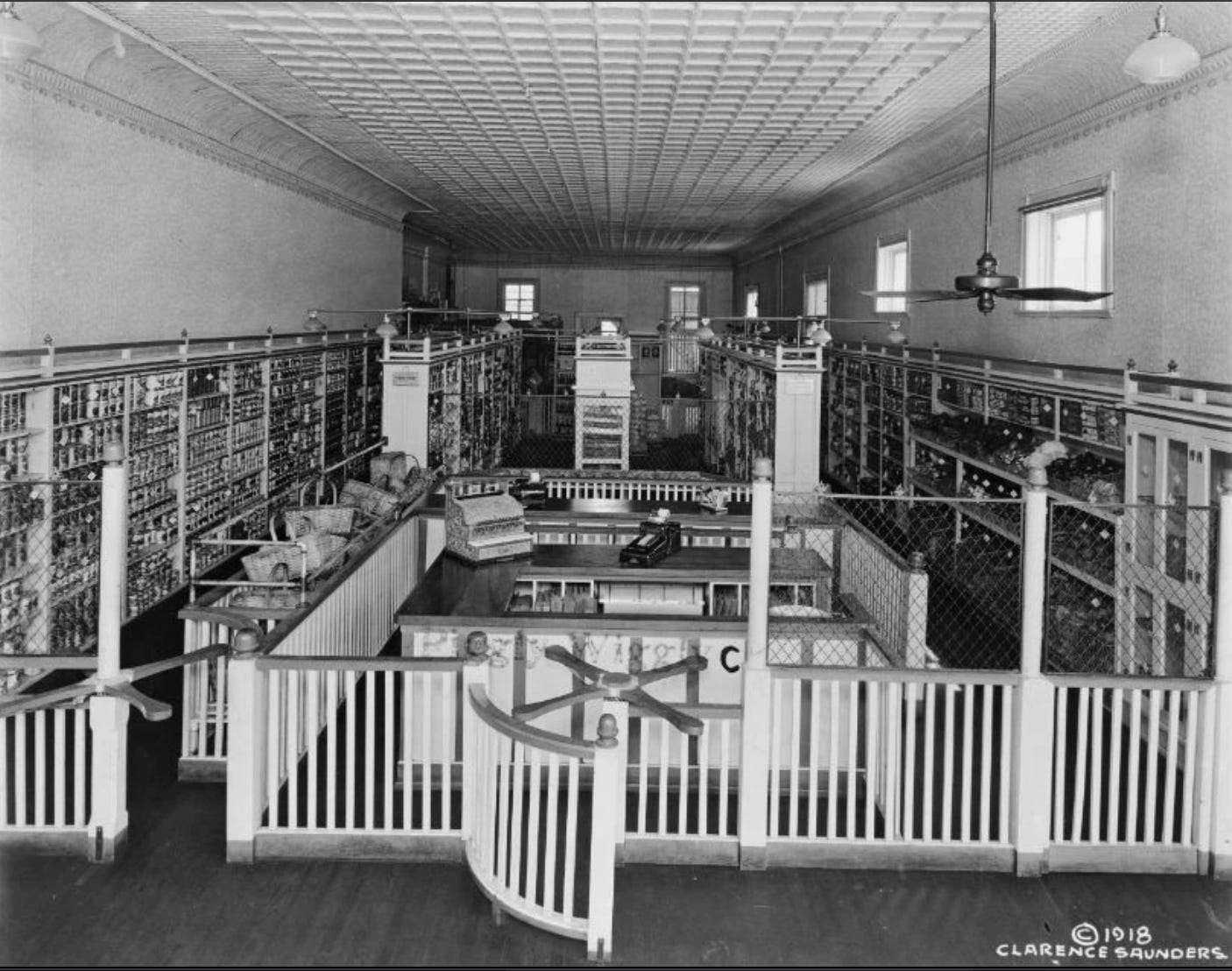

In the imagination of Rattner, Musk, and others in and beholden to the multimillionaire and billionaire class, the fate of the economy depends on whether or not workers trot through turnstiles and accept the return to a life devoted to the workplace. Turnstiles then aren’t just for keeping people out; like the agricultural stiles they were based on, they are for keeping them in for easier yoking. The first modern turnstile is said to have been installed by a retailer for crowd control.

Does the power balance change when employees are freed from office walls of glass, stone, and concrete? The CEOs Rattner talked to seem to think so. Though some companies have implemented surveillance systems allowing them to monitor and control workers to some degree from afar, many believe having workers directly in sight is important—though perhaps mostly to their sense of control. Rattner, the guy famous for charts and graphs, concedes he lacks data to contradict the idea that remote work is productive; business leaders “simply don’t believe it.” Maybe they’re just mad they can't Lumbergh their workers all day.

It’s one thing to ask what employees owe their organizations beyond meeting their job descriptions. It’s an absurdity to ask what they owe the buildings and the investors behind them when the answer is less than zero. Rattner parrots Silicon Valley Bank’s lame excuse that its WFHers were responsible for the bank’s failure (no, really). It’s not the American worker’s job to rescue real estate developers and regional bankers from their failure to diversify or respond to trends or to protect them from the ultra rich instigating bank runs (is not a sentence I ever expected to write).

What those who seek to work off-site (whether all or part of the week) want is flexibility. What’s been highlighted is how very little flexibility most companies have extended to employees in the past (and maybe how little flexibility they have overall, threatening the myth of a nimble private sector). Also laid bare is how much of the health of our economy workers have been sustaining. Industries that point to WFH as a source of revenue woes highlight costs that workers—whether or not the nature of their jobs allows for remote work—usually bear, spending that keeps small and large businesses going. It is employees, not their employers, who usually pay for the cost of commuting, of meals away from home, of work clothes, of child care.

Workers looking for a reasonable work-life balance, for a fair trade of labor for compensation, are not animals to be penned, a mob to be controlled, or claw-handed monsters in the making. Trying to nightmare them into relinquishing any small gains the pandemic’s disruption may have allowed—and pitting one group of workers against another, an actual immoral act—is a refusal to wake up to the new day.