When I applied for secondary teaching jobs after a corporate career, interviewers asked what I would bring from my experience. Some seemed disappointed I didn’t tout my facility with the Microsoft suite. Believing the business world was “light years ahead” technologically and that schools needed to “catch up,” they spoke excitedly of a new era in education about to be ushered in…by PowerPoint.

A quarter century later—perhaps now even more convinced that schools should function like businesses and their main goal is to prep students for work—many districts are being gripped by AI fever. Eager to seem on it, one near me just added a cute chatbot to its website. (Educator Peter Greene explored the silliness of this “AI-in-education awesome sauce” stunt.)

The list of reasons is long—from the practical to the philosophical, pedagogical to ecological, egalitarian and ethical—why teachers may resist being rushed into this latest edtech mania. Education trends and fads, especially tech-related, can be hard to resist, however, even when they run counter to our ideals. Being alert then to messages meant to push or pull us into participating is important.

A set of common messages are coming from a range of sources: tech companies, edtech consultants, AI cheerleaders, early tech adopters, legacy and social media, politicians, pundits, BOEs, admins, colleagues, and parents. Some are implicit; others explicit. Some are easily labelled myths. A few are outright fallacies.

I discuss three here. In part two of this series I’ll cover more.

“AI will save you time!”

Curriculum purveyor Twinkl welcomes you to its “AI hub” with the following: “Empower yourself with our suite of AI-powered tools designed specifically for educators. Designed to save you valuable time so that you can use your energy and expertise where they’ll be most useful - with your students.”

Districts across the US are encouraging teachers to use AI tools such as chatGPT to create lesson plans or to provide instruction, differentiate, create assessments, grade work, and provide feedback to students, all in the interest of productivity.

The recent history of edtech suggests this benefit may well be a pipe dream. In a new study, David T. Marshall, Teanna Moore, and Timothy Pressley found that learning management systems (LMS) sold to schools over the past decade-plus as time-savers aren’t delivering on making teaching easier. Instead, they found this tech (e.g. Google Classroom, Canvas) is often burdensome and contributes to burnout. As one teacher put it, it “just adds layers to tasks.”

In the teens, my district introduced a slew of new systems teachers were required to use even if duplicative of existing systems and one another. They included electronic grade books and homework posting sites that added to our daily load even if they provided some value. Other systems, such as curriculum mapping and teacher evaluation programs, added hours of work while tending to restrict teacher autonomy and creativity, all of which exacerbates burnout.

LMS were intended to alleviate the duller, bureaucratic, peripheral tasks of the job—at which they seem to have largely failed. These systems have also led, as anthropologist Catherine Lutz and I discussed in a chapter of Life By Algorithms: How Roboprocesses Are Remaking Our World, to dehumanizing relationships between admins and teachers and between teachers and students. Electronic open grade books in particular have contributed to the increasingly transactional nature of education. In a recent piece, Seth C. Bruggeman relates how education-as-transaction (I hand in work, maybe plagiarized using AI; you pay me with a grade calculated to the second decimal) is a time-killer that drains trust and motivation.

Now teachers are being prodded to use AI tools to (at least partially) replace some of the most intellectual, creative, core components of the profession. Teachers using chatGPT to produce lesson plans have defended them to me by explaining how they check and fix or flesh them out. Okay, so how much time is saved? And/or, admitting that the quality of what chatGPT produces is lacking, they argue that these tools are going to improve. Okay, so why rush to use it now?

Let’s assume for a moment that AI tools are eventually able to produce great lesson plans and great time savings for teachers. (And let’s set aside that crafting these plans is a key way to get better at teaching.) How will we then expend AI’s promised savings of “energy and expertise”?

Teachers learn fairly early in their careers that when new initiatives are launched, old ones are rarely set aside to make room for them. And when work is taken off our plates, something else gets ladled onto it. So it’s easy to suspect that any time saved (or assumed to be saved) by AI tools will provide permission to add students to rosters and duties to schedules. It may also give permission to replace us entirely: Arizona just approved a virtual, AI-driven, teacher-free charter school. We’ll have plenty of time then.

“You’re avoiding AI out of fear!”

A colleague once suggested I was afraid of change for questioning the value of a new program. Having by then changed careers twice, cities a dozen times, and boyfriends too often, I tried not to let it get under my skin. But teachers who announce they find a new curriculum, system, method, or protocol problematic can be told they’re afraid. This is very much happening with AI.

With this messaging, several -isms can come into play. Veteran teachers who resist AI can be made to feel like old dogs too tired or scared to learn new tricks. Teachers of color concerned about biases being built into AI tools by mostly white designers—what AI research pioneer Dr. Joy Buolamwini calls the “coded gaze”—can be dismissed as overly fearful or as “making everything about race.”

And the three-quarters of teachers who are women are, like women across fields, susceptible to being painted as afraid of AI. The language in a recent Bloomberg article was telling:

If women are more risk-averse and fearful of technology, at least on average, and if an appetite and willingness to adopt new technology is a precondition of being able to thrive in a brave new labor market, generative AI could feasibly exacerbate the gender pay gap.

Hesitant attitudes toward AI here are"risk averse” and fearful" when they could be described as thoughtful, careful, or skeptical. Enthusiasm for AI is cast glowingly as an "appetite" and "willingness” when it could be gullibility, susceptibility to marketing, or disregard for costs and consequences.

In the end, this refrain is little more than an ad hominem attack—and an ironic one at that. It’s trying to scare someone by calling them scared.

“It’s just a tool!” is a variation on this theme that avoiding AI is cowardice. Comparisons are made to slide rules and calculators, typewriters and word processors. When I recently posted on social media something critical of an AI tool for schools, this was one response:

Writer and edtech critic Audrey Watters highlights how much of pro-AI messaging is fear-mongering:

Again, do note this feeling of destabilizing powerlessness that many AI proponents seek to conjure: this story that the world is changing more rapidly than ever before, that this technological change is unprecedented and unavoidable, that you must adopt AI now or you’ll be left behind, that their vision of the future is the only one that offers certainty, security, and safety.

(In Part II, I’ll focus on the idea of AI’s inevitability and the message embedded in the reply pictured above, “You must teach students how to use it ethically!”)

“Using AI makes you a cutting edge teacher!”

This is a counterpart to the fear argument. Just as no one enjoys being perceived as fearful and cowering, few want to feel out of touch—or as though they aren’t one of the cool kids in the know about where the party is. When I spoke to edtech expert, consultant, and former teacher Tom Mullaney for this newsletter, he explained that “FOMO rules everything” when it comes to AI in education.

This message taps into that fear of missing out but is angled toward rewarding AI adopters by labeling them as current and—in our technophilic culture—cool.

A Bluesky poster recently compared AI-reluctant teachers and profs to early hominims using flint tools. To this person (at least it seemed like a real person…) , AI adopters are modern, forward-looking, cutting edge. The resisters by contrast are desperately clinging to the past—and maybe aren’t all that sharp.

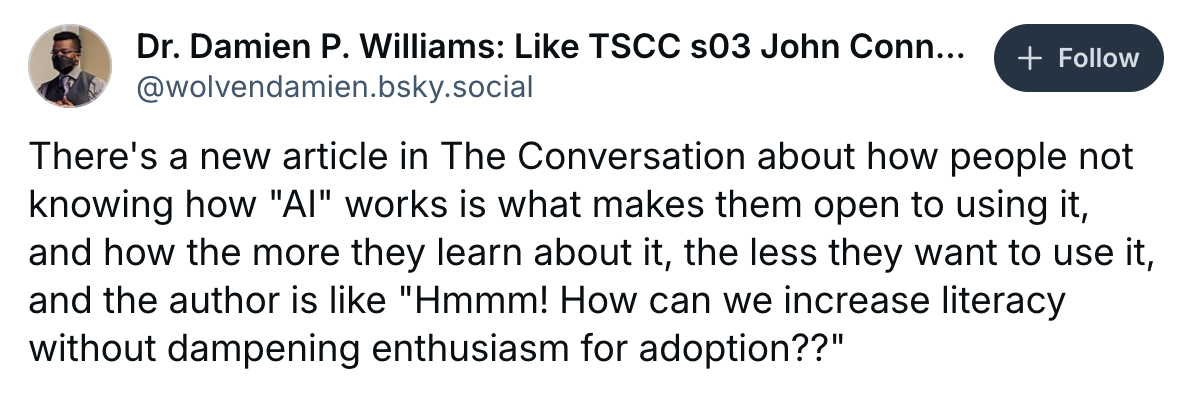

Interestingly, however, a recent study revealed that the more people understand about AI, the less receptive they are to it. Dr. Damien P. Williams summarized it: “…people not knowing how ‘AI’ works is what makes them open to using it, and… the more they learn about it, the less they want to use it.”

Just like the school leaders of 2001 who saw magic in Microsoft Office, some today see magic in AI—in part, this study demonstrated that those who understand it least may see it as the most fantastic in all senses of that word. This may be why many districts and schools are getting teachers to “play”with AI: they don’t know how it works or what it can do for education but they’re convinced it’s the future—and they want teachers to figure it out.

But as I discuss in Part II of this piece, this is not teachers’ core mission but a distraction from it. We have a role to play in preparing students for the future, but this does not necessitate we teach them with or through or to use AI. Our responsibility does extend, in my view, to protecting the planet they will inherit from us—and to resist messages that push us to use tools that threaten it.