Land of Disruption

It's not just the pandemic disrupting learning

As more standardized test results have rolled in this fall, focus continues on the educational disruption caused by the pandemic. Teachers (and those who listen to them) already knew what the data shows: the health crisis has taken a toll on learning, especially on children living in low-income households.

While there is little agreement about how children could have been better protected during this pandemic, the consensus has been strong that avoiding disruptions to schools and learning should be a top priority.

It’s important then to see the pandemic as just one, albeit massive, disruption and to understand that in many ways schools and learning are being increasingly disrupted.

Our failure to provide decent infrastructure disrupts schools and learning.

Students in Jackson, Mississippi spent September, October, and most of November living under a state of emergency, at times learning remotely, because the city was without safe drinking water. The crisis in Jackson, decades in the making, followed the years-long disaster in Flint, MI, where lead in the water was ending up in children’s bloodstreams.

Nationwide, schools are inadequately testing for and addressing lead in water in their buildings, though we've long known how lead can damage children’s physical and cognitive health.

Students across the country have been expected to learn in buildings without adequate HVAC, a fact highlighted by the pandemic of an airborne virus, though working in extreme temperatures alone has been shown to slow learning.

Too many schools are rife with rust or mold, vermin, and other hazards. Overall, US school buildings have received a D+ from the American Society of Civil Engineers. Unsurprisingly, a disproportionate number of lower-income students are educated in bad buildings, environments proven to depress achievement.

Our failure to address climate change disrupts schools and learning.

Many think fondly back on the snow days of their youth, but even areas used to punishing winters are seeing worse storms. The Buffalo, NY area last month received 20 feet of snow in a storm that endangered lives and closed schools for days.

As climate change leads to greater weather extremes and more disasters, it’s not just snow days closing schools: it’s extreme cold days, extreme heat days, ice days, flooding days, wildfire days, and hurricane days that force children from classrooms and can damage schools, rendering them unusable.

At the start of this school year, when Hurricane Ida hit, classrooms across vast regions were damaged or destroyed, sending educators like Kristy McDaniel in Louisiana to crowdfunding sites to replace their contents. Students in Bergen County, NJ are still learning remotely after Ida ravaged their middle/high school. Wildfires led to over 10K school closure days in California from 2015-2019.

Climate change is also pushing students out of the schools where they have established bonds as homes, businesses, and jobs are lost due to conditions such as extended drought, and their families are forced to relocate. This can lead to enrollment declines forcing permanent school closures.

Which students are most affected? As the EPA puts it, that “the most severe harms from climate change fall disproportionately upon underserved communities.”

Our failure to adequately regulate guns disrupts schools and learning.

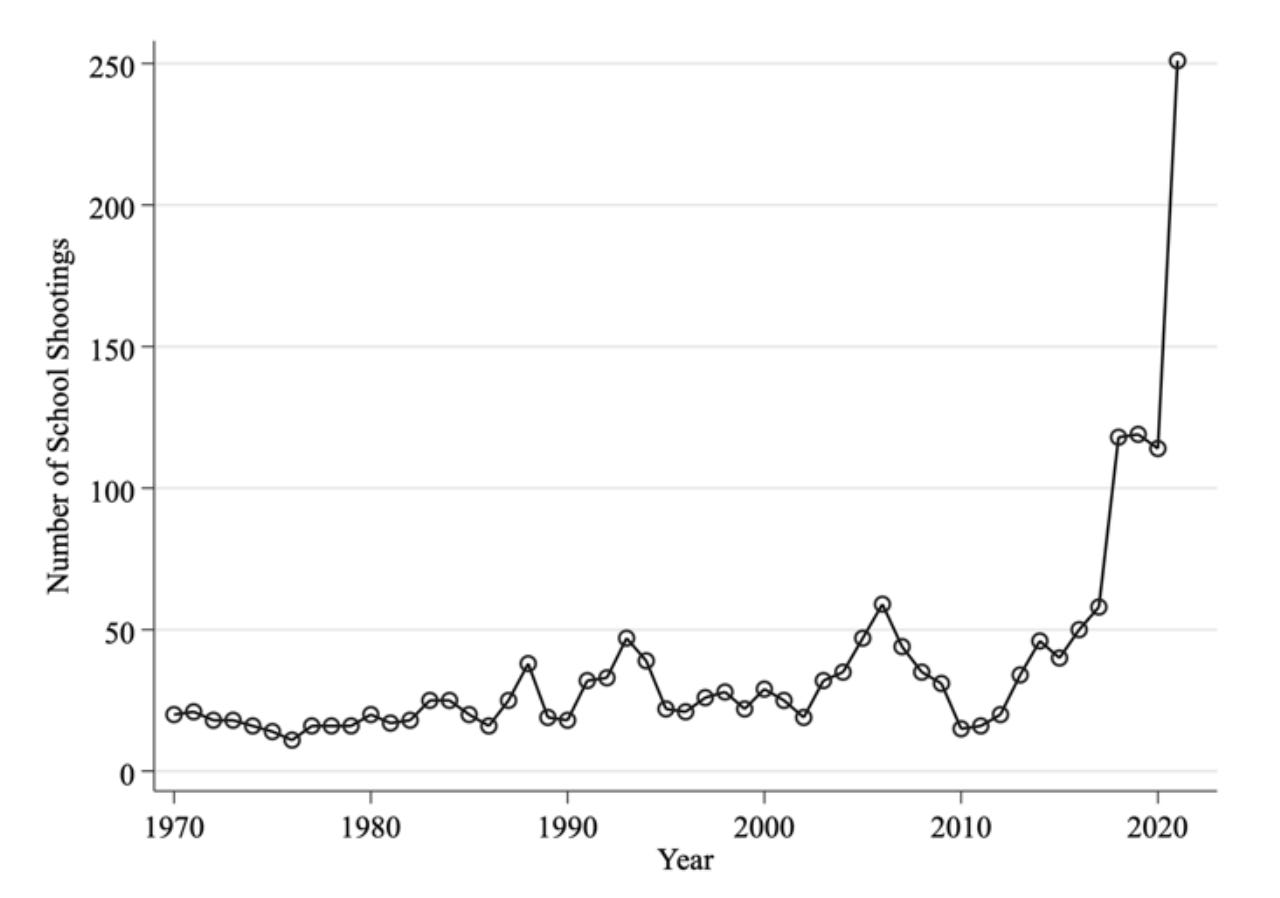

School shootings are worse than ever as this chilling chart shows:

In 2017, The Washington Post highlighted how school shootings affect the killed, the injured, and the “children who witness the violence or cower behind locked doors to hide from it.” And students across the US regularly undergo lockdown drills — a seemingly brief disruption that may keep them safer in the event of a shooting but can create anxiety, even trauma.

Children are not immune from exposure to mass shootings (2022 being the deadliest year yet) and gun violence taking place outside schools (guns are now the leading cause of childhood death).

Increased school closures are resulting from a rash of school shooting threats and hoaxes that can’t be ignored given the easy availability of guns in America, traumatizing school communities.

Unsurprisingly, our gun violence epidemic impacts child mental health and academic achievement. And it is far worse for some: children in higher-poverty counties are four times more likely to die by gun than those in wealthier counties.

There’s more failures where those came from.

Poor infrastructure, rampant gun violence, and accelerating climate change are just a few of the reasons why students are struggling to get to school, stay in school, and attend, engage, and learn in school. (In a future newsletter, I’ll cover more, such as politically-motivated reforms and conflicts and a child mental health crisis decades in the making.) Each of these failures, like the pandemic’s impact, disproportionately hurts children in poverty. Each are caused or, like the pandemic, exacerbated by broader political and social failures.

Asking students to endure them (sit in baking-hot rooms, plan how to avoid being shot) and relying on educators to alleviate them (crowdfund for lost supplies, arm themselves at work), is inadequate and often counterproductive and cruel. Funding and improving infrastructure, battling climate change, and reducing gun violence are urgent tasks that require action by federal and state lawmakers.

Thanks to the pandemic, we have agreed that avoiding disruptions to learning should be an imperative. This should make us look anew at these failures, some quite old and many worsening — and commit to the work outside of schools that needs to be done to ensure children can learn inside them.