Two moments in my teaching career keep coming to mind lately. The first was in the mid-aughts, when my principal said no when I asked if school policy could be crafted to better limit phone use, claiming cell phones were debagged cats. Then in the mid-teens, my department head insisted we integrate, into each lesson, new tech (including phone-based tech such as QR codes) and began rationing copier use.

These memories haunt as a movement grows to reduce children’s overuse of phones, a backlash boosted by adults focused especially on mental health effects, including Jonathan Haidt, whose new book, The Anxious Generation, is receiving much coverage (and some criticism). Schools are experimenting with new ways to keep students off phones, a relief to teachers exhausted from trying to enforce widely-disregarded rules. Common Sense Media found teenagers get hundreds of notifications a day on their phones, many during school hours.

Fortunately, the discussion is being broadened by stakeholders who recognize that cell phone abuse is just part of the tech problem in schools. In a recent piece for The New York Times, Jessica Grose writes about the little evidence we have to support that the time children spend in school on various devices—phones, tablets, and laptops—is improving teaching and learning. As Grose put it:

...there seems to be less chatter about whether there are too many screens in our kids’ day-to-day educational environment beyond the classes that are specifically tech focused. I rarely heard details about what these screens are adding to our children’s literacy, math, science or history skills.

In other words, the problem isn’t just cell phones, and it isn’t just mental health.

When I began teaching high school English in 2000, a PC sat on the teacher’s desk. Videos were shown on a TV rolled into the room via an unwieldy cart. Whiteboards and overhead projectors were core technology. But English classrooms operated primarily on a much older technology: paper.

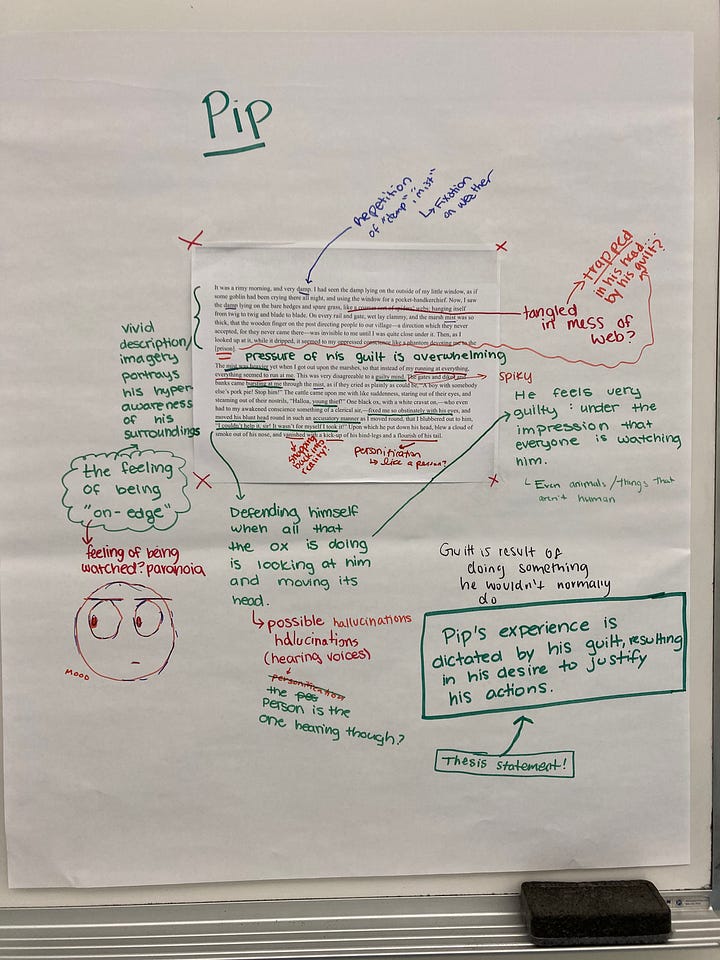

My students read dogeared, Post-it-tabbed paperbacks and discussed them, looking each other in the eye. They gathered over chart paper in small groups, poring over those books, the neatest writer using a Sharpie to display their ideas. They annotated copied passages, competing to see who could use the smallest stub of a pencil. They wrote drafts of essays and stories and poems on lined paper and tore them from spiral notebooks, making confetti. They typed final drafts at home or in the library before putting them in my hands.

This may sound overly nostalgic, but it’s not the reverie of a technophobe. There isn’t space here for me to detail the ways education technology has helped my students, particularly those with special needs. When the pandemic sent us home, the tech resources in my district meant I could continue teaching in a somewhat meaningful way through that remote spring. Teaching this year after a two-year hiatus, I didn’t devolve from electronic files to binders or stop showing students how to conduct online research or refuse to post assignments online.

I did, however, re-embrace the power of paper.

In an electronic world, a paper-based classroom becomes an oasis, a place conducive to focus, quality, and community. By paper-based, I don’t mean one that eschews devices, but one in which paper—not a machine—is the default.

Paper focuses

Focus is foundational. How often while drafting this have I stopped to check email, return a text, or scroll social media? I scheduled a tune-up on the Honda website and entered an HGTV sweepstakes between paragraphs four and five.

So it is, of course, with students, whose work at home and school is interrupted frequently even if their phones are locked and certain websites blocked. Students doing classwork on tablets or laptops can field a flood of IMs, watch March Madness, play games, shop for prom dresses, check their grades, finish homework for other classes. Their attention becomes a many-splintered thing.

By contrast, an analog desktop is focusing. Once students can focus, they can read more closely, carefully, and deeply. A key goal of secondary English teachers is to enable students to read more challenging and complex texts, something facilitated by reading on paper. Students tend to want to read quickly, and as a colleague recently lamented, echoing the research, they often think they are good at skimming—a practice that reading on screens has encouraged—but they aren’t.

Focus enables students to build reading stamina. Worsening reading stamina has been one of secondary English teachers’ key complaints over my career. I’ve written elsewhere about online SparkNotes and some other reasons teens are reading less than they did two decades ago, or even one. A piece this week in The Chronicle of Higher Education offers a mess of possible causes and the sobering voices of college professors frustrated by students less able and willing to read:

Many [college students], they say, don’t see the point in doing much work outside of class. Some struggle with reading endurance and weak vocabulary. A lack of faith in their own academic abilities leads some students to freeze and avoid doing the work altogether.

And a significant number of those who do the work seem unable to analyze complex or lengthy texts.

Stamina is essential, leading to increased comprehension and knowledge, but only, as Stephen Sawchuk points out, if students are reading. One way parents and teachers of secondary students can know is to see actual noses in actual books. When parents complain about a grade, it’s always been worth asking, “Have you seen your child reading the novel we’re studying?” Students can hide from the work of reading behind devices if much of it is delivered that way.

Paper produces

While devices can help us get research, reading, and writing done more quickly, the distractions they bring can also slow us; paper can enable students to get more done in a timely way, especially when it comes to writing. This year, my students wrote first drafts in class and on paper, saving procrastinators and perfectionists untold hours.

This wasn’t my only reason for bringing drafts back in-house. My school, like those across the country, has seen a surge in students submitting writing produced by AI chatbots as their own. The response to this problem varies by school and teacher but often involves more technology. Some are using tech to detect the use of tech; others are pursuing AI training, hoping they can help students use it responsibly.

Going to paper allowed me to avoid the pitfalls of technofixes, avoid presuming I can keep up with the dizzying pace of technological change, avoid embracing or resigning myself to AI in ways I would later regret—something to fear given that AI’s ethical concerns go far, far beyond student plagiarism.

So I battled plagiarism the old-fashioned way, requiring a handwritten first draft that ensured students produced original work before I gave them feedback and reduced their incentive to violate the integrity policy during the revision process. What a fantastic waste of time is students handing in plagiarized work and teachers grading it, never mind what it does to the soul.

There are other, significant benefits of putting pen to paper. Taking notes by hand aids memory, information I’ve been annoying my students with for years when they’ve asked me to post notes online. And NPR recently reported that brain research is revealing more about the value of writing by hand:

Both handwriting and typing involve moving our hands and fingers to create words on a page. But handwriting, it turns out, requires a lot more fine-tuned coordination between the motor and visual systems. This seems to more deeply engage the brain in ways that support learning.

Paper humanizes

To go deep with reading, writing, and thinking, students need time and focus, but they also need the teacher and each other. It’s why English classes depend on discussion, which requires practice and skills that have been affected by heavy tech use.

At times, I’ve used discussion boards and digital annotation tools that can extend conversations outside of school and benefit less confident or quieter students. Some go beyond what can be accomplished on paper, but others simply replicate the kinds of group work that teachers have long facilitated with Post-Its, copier paper, and chart paper. These are especially valuable now as they get students off screens and interacting with each other—and sometimes out of their chairs and moving around the room.

Digital collaboration can be productive; in my experience, analog collaboration has a better chance of being joyful.

As MIT’s Sherry Turkle, author of Alone Together and Reclaiming Conversation, explains, ”It is in this type of conversation — where we learn to make eye contact, to become aware of another person’s posture and tone, to comfort one another and respectfully challenge one another — that empathy and intimacy flourish. In these conversations, we learn who we are.” Face-to-face conversations bring us together in communal attention, remind us of our humanity and the humanity of literary works of art.

Teachers face steep challenges and deep worry about students not reading, not researching, not engaging, not thinking, not creating. These challenges are systemic and widespread. Much is beyond our control. Fighting for healthy, sensible school and district policies (Why did I just accept that “no” back when phones first started proliferating? Why window-dress lessons with tech to please the boss?) is within it. And within the four walls of our classrooms, our daily choices of tools and methods can and do make a difference.

It can be hard to return to the “old.” School leaders and teachers are subject to constant pressure from those who profit from the appeal of the new. Tech firms put their tools in our hands. “Here, try this,” they say. “It’s really cool. It’s the future. It’s your future. It’s your students’ future. Use it. Keep using it.” A teacher friend tells me lined paper is no longer stocked at her school, ostensibly to save money. Meanwhile, the $18.5 billion K-12 ed tech market in the U.S. is expected to grow to $132.4 billion by 2032.

Resisting new ed tech can be hard, especially for veteran teachers, who are vulnerable to stereotyping as stubborn, fearful, or archaic if they persist with or return to tried-and-true methods. Refocusing on my core mission—teaching reading, writing, and thinking—helps me reduce the time I require students to be on screens. Helps me bring out the Sharpies, let them pick a color. Lay in front of them a fresh sheet of paper and all of its promise.