A few years ago, I developed a fiction unit for high school seniors called “This Party Sucks,” built around Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City. It’s a great book to teach: accessible in language, rife with symbolism, and right away grabs the attention of the most reluctant readers:

You are not the kind of guy who would be at a place like this at this time of the morning. But here you are, and you cannot say that the terrain is entirely unfamiliar, although the details are fuzzy. You are at a nightclub talking to a girl with a shaved head. The club is either Heartbreak or the Lizard Lounge. All might come clear if you could just slip into the bathroom and do a little more Bolivian Marching Powder. Then again, it might not.

This month, the novel turns 40. Each time I reread it, I’m brought back to 1984, to my first job out of college, working for peanuts at a book publisher in the Flatiron Building and trying to save enough to move out of my suburban childhood home into a city at once gritty and glamorous, familiar and exotic.

This time, I was struck by how much it anticipated about today.

The Kind of Guy

In the 80s, McInerney was often lumped with Bret Easton Ellis and Tama Janowitz; the trio achieved fame when their works were adapted for films starring the Hollywood Brat Pack. While like most of those actors, McInerney was technically a Boomer, he was seen as a voice of a new generation, Gen X. In Bright Lights, Big City, he captures a precise moment for the microgeneration between the two: the young adulthood of Generation Jones.

My students often noted parallels between the novel and The Great Gatsby. Like many Lost Generation texts, Bright Lights, Big City features a disillusioned and alienated male protagonist. Perennially hungover, he is barely holding onto a dead-end job at a literary magazine, his youthful marriage has abruptly ended, and his nights are desperate quests for drugs and distraction. The fashion model wife who left him—the novel’s Daisy—is portrayed as the embodiment of shallow materialism; the young man is convinced a mannequin in a department store window is based on her, a simulacrum of a simulacrum of a human.

McInerney’s protagonist exhibits a cynicism familiar to those of us who started our careers in the gray of a recession presided over by a Technicolor POTUS, who entered a work world fast disappearing—one with job security, a pension, likely upward mobility—while pop culture extolled the lifestyles of the rich and famous. Nearing rock bottom, the young man is not without a sort of compromised hope. In a telling moment, he buys a suspiciously cheap “Cartier” watch on the street, knowing it’s a probable fake but comforted that it looks real. Maybe it will help him get his life back on track, he thinks. Still, when the watch dies in mere hours, he’s not terribly surprised.

This Kind of Trash

Like the larger culture of the novel, the publishing industry seems in devolution. The protagonist’s job as fact checker in one of the industry’s most venerated institutions is thematically fruitful, as he fails to check facts, yearns to write fiction, and devours the tabloids:

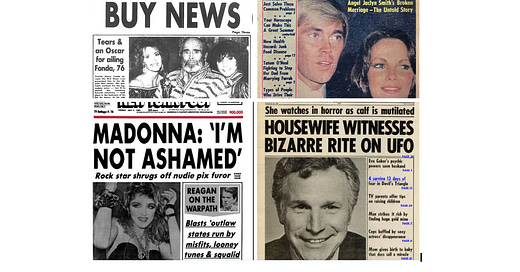

At the subway station you wait fifteen minutes on the platform for a train. Finally a local, enervated by graffiti, shuffles into the station. You get a seat and hoist a copy of the New York Post. The Post is the most shameful of your several addictions. You hate to support this kind of trash with your thirty cents, but you are a secret fan of Killer Bees, Hero Cops, Sex Fiends, Lottery Winners, Teenage Terrorists, Liz Taylor, Tough Tots, Sicko Creeps, Living Nightmares, Life on Other Planets, Spontaneous Human Combustion, Miracle Diets and Coma Babies.

The frenzied, seedy drama of this tabloid universe is a stark contrast to the literary magazine’s stifling offices. Its grotesqueries and conspiracies are a guilty pleasure, another drug providing brief escape from the farcical fastidiousness of his editors. The young man is Gen Jones’s Bartleby; like Herman Melville’s scrivener, his boss would like him to produce, but he will not.

As his editors hew to meticulous standards, the magazine’s writers submit poorly researched essays filled with errors the protagonist can’t correct fast enough. His inability to keep up with these will be his downfall, a plot detail that resonates now, when a “firehose of falsehood” is trained on us 24/7 by politicians, propagandists, and punk pundits—and legacy newspapers cling to long-held journalistic principles that no longer apply.

Looking back, we can see how tabloid culture has gained the edge in the long war between fact and fiction. In Cue the Sun!, her new history of reality television, Emily Nussbaum details how tabloid culture led to newsertainment and to the rise of reality television, both of which helped propel Donald Trump, man of innumerable lies, to the White House.

Writing about how Fox News merged entertainment with reportage and tabloid conspiracies, Nussbaum explains, “That cynical credulity (or credulous cynicism) would become the defining quality of American culture, in the reality genre, on the news, and in politics.”

Bright Lights, Big City hits forty in a year when Donald Trump, avatar of 80s Manhattan excess and agent of 21st-century chaos, was convicted of fraud in a case that illuminated how his rise in business and politics was aided by The National Enquirer, whose ex-publisher David Pecker provided pivotal testimony. Remember that? The news cycle spins so chaotically fast now that May’s unprecedented verdict can seem as distant as years-old tabloid news.

While in some ways McInerney’s tabloid-obsessed protagonist is stuck in the past—he can’t move on from his mother’s death and his marriage’s failure—Bright Lights, Big City is written in the present tense, anticipating the ephemera of social media and its disorienting effect.

“Mixing the internet with reality TV was the speedball of pop culture,” Nussbaum writes. Start scrolling and see what happens to time. A pressing article from two days ago isn’t worth posting; there is no second day for Bean Dad or a dead bear cub. The tabloidization of everything produces the feeling of existing in a swirling ever-present.

Do I Know It’s Real

Some of the best class discussions of the novel focused on its use of the second-person point of view. My students were familiar with unreliability in first-person narrators; they understood Fitzgerald’s Nick Carraway is unreliable. He does not know what is in Gatsby’s past or in his head; he subtly and unsubtly judges all. But Nick observes Gatsby from the outside, while Bright Lights, Big City’s protagonist observes himself that way. He’s so detached that he’s outside himself, a self-conscious onlooker to his own life—not so different from how we produce and consume our identities on social media.

“How do I know it’s real?” the protagonist asks the hustler hawking watches before plunking down his cash. “How do I know it’s real?” is a question we ask with alarming frequency in the age of influencers and reality stars who stage their lives, the age of social media platforms filled with bots, the age of AI-generated videos—sometimes right before we hit REPOST.

This summer has shown how desperately many Americans want to shake the past (We’re not going back! We’re not going back!) and escape the mire of the present (These same two men? This party sucks!) and move forward. More see a future. Like McInerney’s protagonist, we hadn’t fully given up hope. Yes, “You are the kind of guy who always hopes for a miracle at the last minute.”

At novel’s end, the protagonist experiences hope in a warm piece of bread at dawn’s light, a nourishing hope that brings peace with the past and points to the future. The future won’t be delivered by miracle alone but through the hard work of reconnecting, of being human: “You will have to go slowly. You will have to learn everything all over again.”