With back-to-school ads everywhere, I’m reminded of last summer, when we faced a wave of contrarian takes that media alarm about the teacher shortage was undue.

“There is No National Teacher Shortage,” announced Derek Thompson at The Atlantic. “Researchers Say Cries of Teacher Shortages are Overblown” read another headline. A flurry of other commentary questioned its scope and seriousness.

A year after we were told to calm the hell down, a new report by RAND Corporation and the Center on Reinventing Public Education at Arizona State University highlights some of the effects of a very real crisis, a slow-rolling one that picked up speed with the pandemic and with counterproductive approaches to the problem of too few qualified teachers working in classrooms.

The authors of the new report admit that their information, garnered from interviews with a handful of district leaders about their pandemic academic recovery plans, gives just a glimpse of a complex national picture. Nevertheless, these administrators’ words provide support for concerns teachers have been raising about their profession for well over a decade.

What we’ve been saying:

Teacher pay, respect, and working conditions have declined to the point where far too few young people and career changers want to enter the profession.

What the administrators said:

In good part, they blamed their inability to reach their goals on difficulties finding and hiring teachers from the small pool available. Teaching suffered as a result.

[S]chool system leaders said that many of their teachers were some combination of new, young, and less experienced. In three out of our five school systems, leaders reported that these problems stemmed from a tight teacher labor market—they did not have the luxury of hiring only the highest-quality teaching candidates. “The pipeline is so much smaller that we're taking risks and bets on potential teachers that are not always working out,” one leader said. “I do think the first and foremost issue is ‘Do we have enough high quality teachers in our schools to do this work?’ And the answer is no right now for us. And that's a really hard thing to say, but I think that is the reality. To staff their classrooms, these systems had to hire more "nontraditional" or "non-credentialed" teachers, or teachers from alternate pathways that typically do not include a teaching degree, as administrators pin the blame for poor achievement results on their difficulties in hiring and their overreliance on inexperienced teachers…”

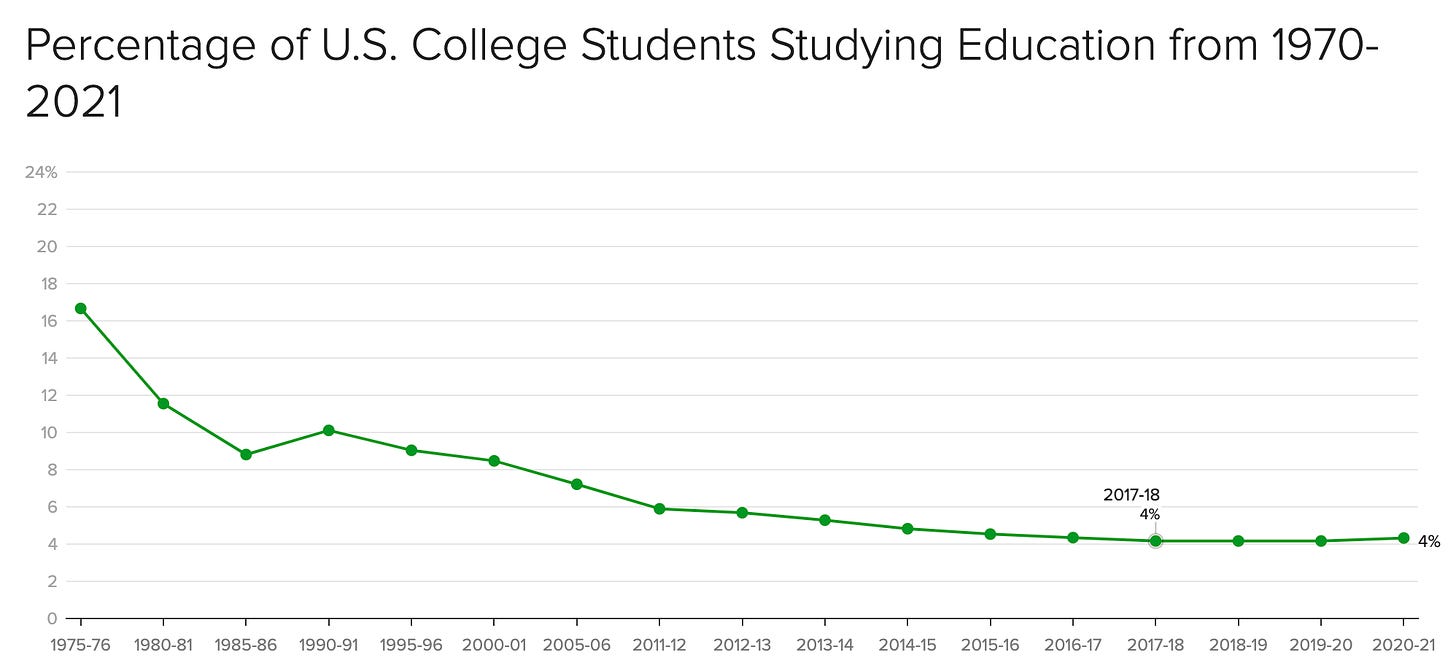

The chart below from a CBS report this week demonstrates the long upside-down arc of the recruiting and hiring crunch. Women flooded into better-paying careers in the 1970s. The launch of No Child Left Behind in 2000—and the steady drumbeat of teacher bashing and years of stifling austerity that followed—led to further decline.

In lieu of addressing root causes, some states responded to the pipeline problem by eliminating requirements and loosen credentialing, an obviously terrible way to recruit high quality teachers, one that the RAND report points out also requires districts to provide more training.

What we’ve been saying:

Teacher pay, respect, and working conditions have declined to the point where too many teachers are willing to quit or retire early.

What the administrators said:

Though the report does not mention the excess loss of experienced teachers in the years leading up to and at the start of the pandemic, or the historically high turnover of new teachers, it describes teachers less able to finish school years before leaving a district or the profession, reflecting worsened conditions:

Other leaders discussed the challenges of teachers quitting mid-year as a new phenomenon, or quitting after a week. Other teachers had staged walk-outs at individual schools to protest working conditions.

CNN recently provided data showing that teachers are quitting more than they are being laid off or retiring. It reviews some reasons why this is the case, including low pay, violence, and burnout. Teachers and potential teachers had too many reasons to not teach well before Covid-19 reached our shores. Last winter, Brown’s Matthew Kraft and University of Albany’s Melissa Arnold Lyon revealed trends in teacher dissatisfaction in the decades leading up to and into the pandemic:

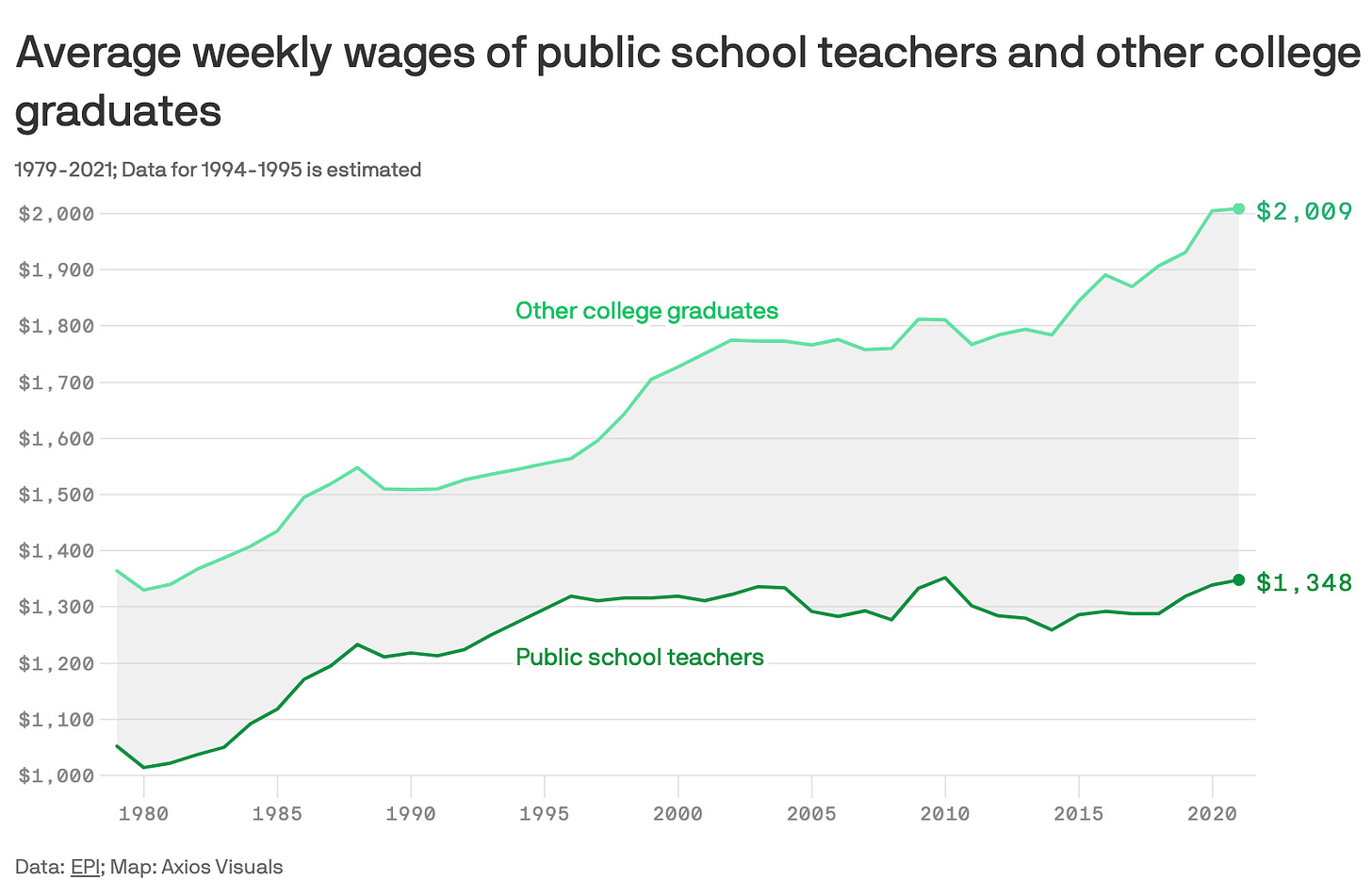

While job satisfaction and enthusiasm has declined, teacher salaries have been stagnant for a quarter century, rising $29 on an inflation-adjusted basis since 1996. The only trend line up: stress.

What we’ve been saying:

Teacher pay, respect, and working conditions have declined to the point where too many teachers are unable to perform to the best of their ability.

What the administrators said:

Leaders noted a change in teachers’ capacity to take on more work—they knew their teachers were “exhausted,” and they worried about asking them to do more…..Leaders in four out of our five school systems also noted higher levels of teacher burnout…Most leaders said they recognized the toll the pandemic took on teachers’ mental health, which they saw as a barrier to asking them to do anything extra.

It’s on this point that the RAND report takes its turn toward blaming teachers, using and quoting language suggesting they may simply be shirking the work necessary to help struggling students. (I’ve bolded some of this language.)

For example, teachers were less committed to attending professional learning sessions or staying after school to support students or attending meetings, stipend or not. One leader elaborated that in their school system, “teacher appetite for engaging in professional learning outside of the school day [has not returned. Teachers] really just aren’t attending…”

It’s worth noting that teachers have long found the professional development they are offered to be wanting. The report admits that some school leaders “struggled to find and hire high-quality professional learning providers” and “were quite disappointed in the quality of support they received from vendors.” This isn’t new. Back in 2014, the Gates Foundation found only 3 out of 10 teachers were satisfied with their PD.

Setting that aside, overburdened teachers being unwilling or unable to add more to their plates after years of having more added to those same plates is a natural consequence of pretending they can always do more with less. A report last year showed teachers were twice as stressed as workers in other fields. There is a tipping point when burnout becomes burned out. And many educators have reached it.

I am one of the teachers who exited teaching early in the pandemic, at the end of the 2020-2021 school year, during which I had taught in person for all but a few weeks. It was, unsurprisingly, the most difficult year of my 20-year career and certainly not the joyous final year I had held in my imagination. But I suspected the coming years could be worse, not just due to the mental health and academic challenges of the pandemic but due to the acceleration of other trends, including the politicization of curriculum and demonization of teachers.

When I spoke to my former colleagues that next year, 2021-2022, every one said that it was harder than the last. I heard this from teachers in other schools and other parts of the country as well. With near universality, they reported that what helped make it so difficult was feeling that they were not able to teach to the best of their ability.

The RAND report focuses on the need to improve student achievement. It provides meaningful feedback from school leaders on why they believe they failed to deliver on their pandemic recovery plans. It focuses on the need for strong and sustained professional development around instruction. It recognizes that all constituencies need to play a role.

Yet at the same time as the report files the complaint that teachers are “falling back on outdated and ineffective methods,” its authors fall back on outdated caricatures of teachers and muted recommendations.

If there is one thing that the report makes clear it is that the teacher shortage is interfering with improving student achievement. Absent from their recommendations are solutions to the shortage’s root causes, including paying teachers competitively and meaningfully battling teacher burnout. Though it has many sources, ignoring this burnout—or mischaracterizing it as checking out—is not going to make it go away.

We should be alarmed, but we can’t be surprised. The crisis in teaching, a crisis leading to, arising from, and bigger than the teacher shortage, has been building for a long time. During that time, many of the solutions tried have been weak, wrong-headed, even counterproductive. Making the profession attractive and sustainable must be the goal. If that sounds familiar, it’s not just me. Teachers have been saying it for years.